I finally got around to reading James Surowiecki’s “What does procrastination tell us about ourselves?” (answer: maybe nothing; maybe a lot), which has been going around the Internet like herpes for a very good reason: almost all of us procrastinate, almost all of us hate ourselves for procrastinating, and almost all of us go back to procrastinating without really asking ourselves what it means to procrastinate.

According to Surowiecki, time preferences help explain procrastination. For a good introduction on the topic, see Philip Zimbardo and John Boyd’s The Time Paradox. The short, non-technical version: Some people tend to value present consumption more than future consumption, while others are the inverse. And it’s not just time preferences that change who we are; as Dan Ariely documents in Predictably Irrational, we also change our stated behaviors based on whether, for example, we’re aroused. We also sometimes prefer to bind ourselves through commitments to deadlines or to external structures that will “force” us to behave a certain way. How many dissertations would be completed without the social stigma that comes from working on a project for years and failing to complete it, coupled with the threat of funding removal?

The basic issue is that we have more than one “self,” and the self closest to the specious present (which lasts about three seconds) might be the “truest.” This comes out in the form of procrastination. To quote at length from Surowiecki, who is nominally reviewing The Thief of Time: Philosophical Essays on Procrastination:

Most of the contributors to the new book agree that this peculiar irrationality stems from our relationship to time—in particular, from a tendency that economists call “hyperbolic discounting.” A two-stage experiment provides a classic illustration: In the first stage, people are offered the choice between a hundred dollars today or a hundred and ten dollars tomorrow; in the second stage, they choose between a hundred dollars a month from now or a hundred and ten dollars a month and a day from now. In substance, the two choices are identical: wait an extra day, get an extra ten bucks. Yet, in the first stage many people choose to take the smaller sum immediately, whereas in the second they prefer to wait one more day and get the extra ten bucks.

In other words, hyperbolic discounters are able to make the rational choice when they’re thinking about the future, but, as the present gets closer, short-term considerations overwhelm their long-term goals. A similar phenomenon is at work in an experiment run by a group including the economist George Loewenstein, in which people were asked to pick one movie to watch that night and one to watch at a later date. Not surprisingly, for the movie they wanted to watch immediately, people tended to pick lowbrow comedies and blockbusters, but when asked what movie they wanted to watch later they were more likely to pick serious, important films. The problem, of course, is that when the time comes to watch the serious movie, another frothy one will often seem more appealing. This is why Netflix queues are filled with movies that never get watched: our responsible selves put “Hotel Rwanda” and “The Seventh Seal” in our queue, but when the time comes we end up in front of a rerun of “The Hangover.”

The lesson of these experiments is not that people are shortsighted or shallow but that their preferences aren’t consistent over time. We want to watch the Bergman masterpiece, to give ourselves enough time to write the report properly, to set aside money for retirement. But our desires shift as the long run becomes the short run.

This probably explains why you have to like the daily process of whatever you’re becoming skilled at (writing, researching, law, programming) in order to get good at it: if you have a very long term goal (“Write a great novel” or “Write an entire operating system”), you’ll probably never get there because it’s very easy to defer that until tomorrow. But if you break the task down (I’m going to write 500 words today; I’m going to work on memory management) and fundamentally like the task, you might actually do it. If your short-term desires roughly align with your long-term desires, you’re doing something right. If they don’t, and if you can’t find a way to harmonize them, you’re going to be the kind of person who looks back in 20 years and says, “Where did the time go?”

The answer is obvious: minute by minute and second by second, into activities that don’t pass what Paul Graham calls “The obituary test” in “Good and Bad Procrastination” (like many topics others pass over, he’s already thought about the issue). Are you doing something that will be mentioned in your obituary? If so, then you’re doing something right. Most of us aren’t: we’re watching TV, hanging out on Facebook, thinking that we really should clean the house, waiting for 5:00 to roll around when we get off work, thinking we should go shopping for that essential household item. As Graham says, “The most impressive people I know are all terrible procrastinators. So could it be that procrastination isn’t always bad?” It isn’t, as long as we’re deferring something unimportant for something important, and as long as we have appropriate values for “important.”

So how do we work against bad procrastination and towards doing something useful? The question has been on my mind lately, because a friend who’s an undergrad recently wrote:

A lot of my motivation comes from a fantasy of myself-as-_____, where the role that fills the blank tends to change erratically. Past examples include: writer, poet, monk, philosopher, womanizer. How long will the physicist/professor fantasy last?

I replied:

This is true of a lot of people. One question worth asking: Do you enjoy the day-to-day activities involved with whatever the fantasy is? For me, the “myself-as-novelist” fantasy continues to be closer to fantasy than reality, although “myself-as-writer” is definitely here. But I basically like the work of being a novelist: I like writing, I like inventing stories, I like coming up with characters, plot, etc. Do I like it every single day? No. Are there some days when it’s a chore to drag myself to the keyboard? Absolutely. And I hate query letters, dealing with agents, close calls, etc. But I like most of the stuff and think that’s what you need if you’re going to sustain something over the long term. Most people who are famous or successful for something aren’t good at the something because they want to be famous or successful; they like the something, which eventually leads to fame or success or whatever.

If you essentially like the day-to-day time in the lab, in running experiments, in fixing the equipment, etc., then being a prof might be for you.

One other note: writer, poet, and philosopher have some aspect of money involved in it. So does physicist / professor. Unless you’re Neil Strauss or Tucker Max, “womanizer” is probably a hobby more than a profession. And think of Richard Feynman as an example: he sounds like he got a lot of play, but that wasn’t his main focus; it’s just something he did on the side, so to speak. (“You mean, you just ask them?!”). The more you have some other skill (being a writer, a rock star, whatever), the easier it seems to be to find members of your preferred sex to be interested in you. In Assholes Finish First, Max notes that women started coming to him after his website became successful (note that I have not had the same experience writing about books and lit).

As for the physicist/prof fantasy, I have no idea how long it will last. You sound like you’re staying upwind, per Paul Graham’s essay “What You’ll Wish You’d Known“, which is important because that will let you re-deploy as time goes on. To my mind, read/writing and math are upwind of almost everything else; if you work on those two – three subjects, you’ll probably be okay.

One nice thing about grad school in physics is that you can apparently leverage that to do a lot of other things: programming; becoming a Wall Street quant; doing various kinds of business analysis; etc. It’s probably a better fantasy than monk, poet, or philosopher for that reason. The “philosopher” thing is also (relatively) easy to do on the side, and I would guess it’s probably more fun writing a philosophy blog than writing peer-reviewed philosophy papers, which sounds eminently tedious, at least to me.

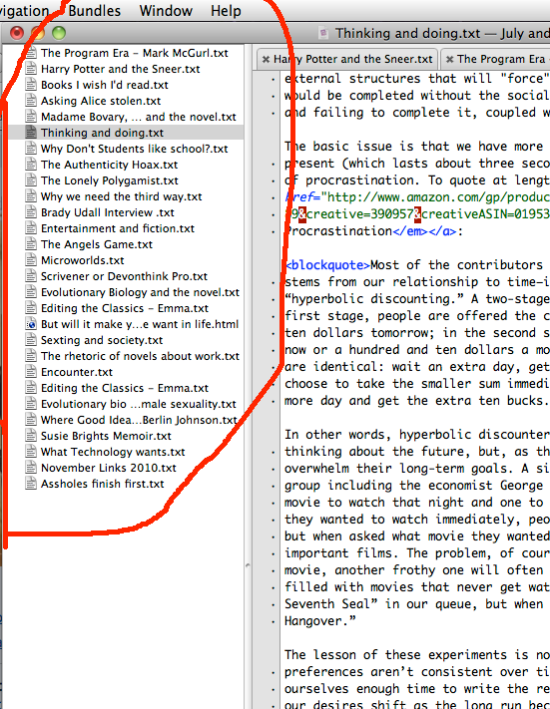

Oh: and I have a pile of unposted, half-written blog posts in my Textmate project drawer:

You can see a pile of them on the left. Most will eventually get written. Some will eventually be deleted. All were started with good intentions. Some have been sitting there for a depressingly long period of time. In fact, this post might have found its way among them, if not for the fact that I decided to write it in a single blaze of activity, and if not for the fact that I’m writing about procrastination, this post might have gone the way of many others: half-finished and eventually abandoned.

One reason I’ve had staying power with this blog, while so many of my friends have written a blog for a few months and then quit, is because I basically like blogging for its own sake. Blogging hasn’t brought me fame, power, money, groupies, or other markers of conventional success (so far, anyway!), and it appears unlikely to do so in the short- to medium-term (the long term is anyone’s guess). Sometimes I worry that blogging keeps me from more important work, like writing fiction, but I keep doing it because I like it and because blogging teaches me a lot about the subject I’m writing about and is an excellent forum for small ideas that might one day grow into much larger ones. This is basically the issue that “Signaling, status, blogging, academia, and ideas” discusses.

If the small projects lead to the big projects, you’re doing something right. If the small projects supplant, instead of supplementing, the big projects, you’re doing something wrong. But if you don’t like the small increments of whatever you’re working on, you’re not likely to get to the big project. You’re likely to procrastinate. You’re likely to skip from fantasy to fantasy instead of finding your place. You’re not likely to do the right kind of procrastinating. I wish I’d realized all this when I was younger. Of course, I wish I’d learned a lot of things when I was younger, but I didn’t have Surowiecki, Graham, Zimbardo, Max, and Feynman. Now I do, which enables me to say, “this blog post itself is a form of procrastination, but a productive one, and it’s therefore one I’m going to finish because I like writing it.” That sure beats improbable resolutions.