Golden Hill might be the most amazing novel I’ve read since Lonesome Dove: after a string of duds I’m pleased to find a novel so cleverly written and plotted. The latter point matters: every time Golden Hill seems to be too pleased with its own reproduction of eighteenth-century language, a shocking turn reminds one of the stakes, and that the novel is not primarily an exercise in language mimicry (though it is that too, and pleasingly). Laura Miller’s review induced me to it, though the review doesn’t and maybe can’t give a good sense of just how delightful the book is. Most of us who aren’t seeking tenure won’t care how much it relates to 18th Century antecedents or 20th Century recreations of those antecedents; we care if the book is any good and gives pleasure, and it does. The machinations of money and money transfer drive the plot: has the first great novel that turns on Bitcoin or Ethereum been written, yet? Long before digital coinage, Mr. Smith shows in New York, in 1746, and says little of himself, but he presents a bill for cash. The counting-house man, Mr. Lovell, wants to know, as does the reader, “What is this thing? And who are you?” Smith says, “What it seems to be. What I seem to be. A paper worth a thousand pounds; and a traveler who owns it.” The dialogue on the pages that follow is a witty duel, and Lovell reminds Smith that “Commerce is trust, sir. Commerce is need and need together, sir.” Can Smith and Lovell trust each other? And why? The trust is not only commercial but romantic and sexual as well: Lovell has a pair of daughters, who are intrigued by this curious man, who is rich—or is he? If he is attempting to steal money, what else might he attempt to steal?

The sentences satisfy, and the style is winkingly old, with many clauses strung together: “As a mason must build a wall one brick at a time, though the finished wall be smooth and sheer, so in individual pieces did Mr. Smith’s consciousness return to him, the next day, as he lay in the truckle bed of Mrs. Lee’s gable-end bedroom, and assembled the world again.” Or: “Mr. Lovell, to whom few things retained the force of novelty, and who misliked extremely the sensation when they did, as if firm ground underfoot had been replaced on the instant by a scrabbling fall in vacuo—was, at the moment the door opened on Broad Way, hesitating in his parlour.” We learn much about Mr. Lovell, there, and why he may be unusually suspicious of Smith, whose novelty continues through the novel. He is busy watching others, but he “failed to perceive, as he reflected and considered, that others were meanwhile reflecting and considering upon him.” His perspective seems stable at first, but he is often surprised, as his own assumptions about others prove wrong. First impressions are often dashed, as are second-, third-, and fourth impressions. The best impression of the novel may be not the first time through but the second, when what seem to be minor, though depressing, details, like Smith noticing “a coffle of shuffling black men in irons underscoring the street music with a dismal clank.”

Still: antecedents. Golden Hill reminds me of John Barth’s The Sot-Weed Factor, though Golden Hill is blessedly shorter. The Sot-Weed Factor is amazing, but too many plot turns leaves one reeling and discombobulated, like an excess of drink; as with many things is life, some is good and too much is not better, and by the midpoint of The Sot-Weed Factor a yearning for resolution sets in, and tedium overcomes investment. Like Golden Hill, it decides to situate, as best it can, the reader in the mind of a man from centuries ago. There is much happening in Golden Hill’s many metaphors. Septimus tells Smith, “the ships come and go again, and the most part of the traffic of souls passes straight through. They walk up from the slips to the streets and are gone; the continent devours them. New-York is but a gullet. Few stay.” “A gullet:” a piece of the digestive track, and few of us wish to be subjected to digestion. The New World was brutal, then. Death everywhere, and, horribly, “we have no theatre” in New York. Naturally, a play is eventually got up, and plays into the rest of the book, which is braided tightly together, the early parts reappearing in the later.

The way Golden Hill speaks of today’s dilemmas garbed in the past is interesting, but maybe most interesting is the way that it, like The Name of the Rose, is a text composed of other texts, and made the better for it. The hook, though, remains the plot: it is in motion, with the plays within plays within plays, and political theater and theater theater are much the same—as they are today and likely will be tomorrow. Each time I felt sure-footed reading Godlen Hill, something shifted, and left me off balance, in a way that’s hard to describe easily felt as a reader. I didn’t foresee the ending, though it seems obvious in retrospect: a bit ridiculous, and with some unlikely elements, but it fits. “Where do you get your ideas?” is among the least good questions that can be asked, and yet this novel combines elements so unexpectedly that I’d like to ask its author about them.

The book is about a girl’s affair with a married man, and she kinda sorta tries polyamory lite, but without thinking much about it or having any social or community structure for it. Conversations a “kinda sorta” sort of book, which is why it’s so unsatisfying. The sentences are short and it’s easy to skip sentences, paragraphs, pages, without losing anything. Still, Conversations gives hope to unpublished writers, because if it can get published and pushed, you might be able to too.

The book is about a girl’s affair with a married man, and she kinda sorta tries polyamory lite, but without thinking much about it or having any social or community structure for it. Conversations a “kinda sorta” sort of book, which is why it’s so unsatisfying. The sentences are short and it’s easy to skip sentences, paragraphs, pages, without losing anything. Still, Conversations gives hope to unpublished writers, because if it can get published and pushed, you might be able to too. A hardboiled French detective (or “Superintendent,” which is France’s equivalent) must team up with a humanities lecturer to find out, because in the world of The Seventh Function it’s apparent that a link exists between Barthes’s work and his murder. They don’t exactly have a Holmes and Watson relationship, as neither Bayard (the superintendent) or Herzog (the lecturer) make brilliant leaps of deduction; rather, both complement each other, each alternating between bumbling and brilliance. Readers of The Name of the Rose will recognize both the detective/side-kick motif as well as the way a murder is linked to the intellectual work being done by the deceased. In most crime fiction—as, apparently, in most crime—the motives are small and often paltry, if not outright pathetic: theft, revenge, jealousy, sex. “Money and/or sex” pretty much summarizes why people kill (and perhaps why many people live). That sets up the novel’s idea, in which someone is killed for an idea.

A hardboiled French detective (or “Superintendent,” which is France’s equivalent) must team up with a humanities lecturer to find out, because in the world of The Seventh Function it’s apparent that a link exists between Barthes’s work and his murder. They don’t exactly have a Holmes and Watson relationship, as neither Bayard (the superintendent) or Herzog (the lecturer) make brilliant leaps of deduction; rather, both complement each other, each alternating between bumbling and brilliance. Readers of The Name of the Rose will recognize both the detective/side-kick motif as well as the way a murder is linked to the intellectual work being done by the deceased. In most crime fiction—as, apparently, in most crime—the motives are small and often paltry, if not outright pathetic: theft, revenge, jealousy, sex. “Money and/or sex” pretty much summarizes why people kill (and perhaps why many people live). That sets up the novel’s idea, in which someone is killed for an idea. There’s a lot of great dialogue, which I can be a sucker for:

There’s a lot of great dialogue, which I can be a sucker for: *

*  I don’t want to spoil those surprises; if the regular writerly bildungsroman is about books progressively emerging, this one is about the ambition monster getting progressively bigger, like a dragon, until it eats its owner. Or does the owner thrive at the end? I can’t say more here.

I don’t want to spoil those surprises; if the regular writerly bildungsroman is about books progressively emerging, this one is about the ambition monster getting progressively bigger, like a dragon, until it eats its owner. Or does the owner thrive at the end? I can’t say more here. If you’ve not read about this period and these systems, go ahead and

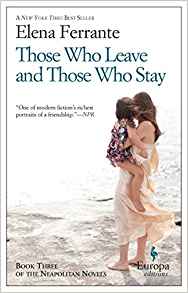

If you’ve not read about this period and these systems, go ahead and  Yet those long sections end and move back into the specific and personal (“it was a chain with larger and larger links: the neighborhood was connected to the city, the city to Italy, Italy to Europe, Europe to the whole planet. And this is how I see it today: it’s not the neighborhood that’s sick, it’s not Naples, it’s the entire earth”). Elena, the protagonist, is pleased at one point that “I had married a respectable man.” But “respectable” to her transmutes to “predictable” and thus boring: is that the way of most relationships today?* One wonders: every strength has a weakness and the sameness of “respectable” is dull to her and, she feels, dulls her. Respectable is a word that connotes a person’s character in the eyes of an imagined community, rather than the eye and mind of a single individual. To the community respect may be valuable. To Elena it becomes a drag. She needs to re-start the relationship process, which is charted in so many novels (one favorite is

Yet those long sections end and move back into the specific and personal (“it was a chain with larger and larger links: the neighborhood was connected to the city, the city to Italy, Italy to Europe, Europe to the whole planet. And this is how I see it today: it’s not the neighborhood that’s sick, it’s not Naples, it’s the entire earth”). Elena, the protagonist, is pleased at one point that “I had married a respectable man.” But “respectable” to her transmutes to “predictable” and thus boring: is that the way of most relationships today?* One wonders: every strength has a weakness and the sameness of “respectable” is dull to her and, she feels, dulls her. Respectable is a word that connotes a person’s character in the eyes of an imagined community, rather than the eye and mind of a single individual. To the community respect may be valuable. To Elena it becomes a drag. She needs to re-start the relationship process, which is charted in so many novels (one favorite is