Over in the Seattle section of Reddit someone asked, “Millennials of Seattle: Do you believe that you have a future in this city?”* My answer started small but grew until it became an essay in and of itself, since “Seattle” is really a stand-in for numerous other cities (like NYC, LA, Denver, and Boston) that combine strong economies with parochial housing policies that cause the high rents that hurt younger and poorer people. Seattle is, like many dense liberal cities, becoming much more of a superstar city of the sort Edward Glaeser defines in The Triumph of the City. It has a densely urbanized core, strong education facilities, and intense research, development, and intellectual industries—along with strict land-use controls that artificially raise the cost of housing.

Innovation, in the sense Peter Thiel describes in Zero to One, plus the ability to sell to global markets leads to extremely high earning potential for some people with highly valuable skills. But, for reasons still somewhat opaque to me and rooted in psychology, politics, and law, (they’re somewhat discussed by Glaeser and by Tyler Cowen in Average is Over), liberal and superficially progressive cities like Seattle also tend to generate the aforementioned intense land-use controls and opposition to development. This strangles housing supply.

The combination of high incomes generated by innovation and selling to global markets, along with viciously limited housing supply, tends to price non-superstars out of the market. Various subsidy schemes generate much more noise than practical assistance for people, and markets are at best exceedingly hard to alter through government fiat. So one gets periodic journalistic accounts of supposed housing price “crises.” By contrast to Seattle, New York, or L.A., Sun Belt cities are growing so fast and so consistently because of real affordable housing. People move to them because housing is cheap. Maybe the quality of life isn’t as high in other ways, but affordability is arguably the biggest component of quality of life. Issues with superstar cities and housing affordability are well-known in the research community but those issues haven’t translated much into voters voting for greater housing supply—probably because existing owners hate anything that they perceive will harm them or their economic self-interests in any way.

Somewhat oddly, too, large parts of the progressive community seem to not believe in or accept supply and demand. Without understanding that basic economic principle it’s difficult to have an intelligent discussion about housing costs. It’s like trying to discuss biology with someone who neither understands nor accepts evolution. In newspaper articles and forum threads, one sees over and over again elementary errors in understanding supply and demand. I used to correct them but now mostly don’t bother because those threads and articles are ruled by feelings rather than knowledge, per Heath’s argument in Enlightenment 2.0, and it’s mentally easier to demonize evil “developers” than it is to understand how supply and demand work.

Somewhat oddly, too, large parts of the progressive community seem to not believe in or accept supply and demand. Without understanding that basic economic principle it’s difficult to have an intelligent discussion about housing costs. It’s like trying to discuss biology with someone who neither understands nor accepts evolution. In newspaper articles and forum threads, one sees over and over again elementary errors in understanding supply and demand. I used to correct them but now mostly don’t bother because those threads and articles are ruled by feelings rather than knowledge, per Heath’s argument in Enlightenment 2.0, and it’s mentally easier to demonize evil “developers” than it is to understand how supply and demand work.

Ignore the many bogeymen named in the media and focus on market fundamentals. Seattle is increasingly great for economic superstars. Most of them probably aren’t wasting time posting to or reading Reddit. If you are not a superstar Seattle is going to be very difficult to build a future in. This is a generalized problem. As I said earlier, voters don’t understand basic economics, and neither do reporters who should know better. Existing property owners prefer to exclude rivalrous uses. So we get too little supply and increasing demand—across a broad range of cities. Courts have largely permitted economic takings in the form of extreme land-use control.

Seattle is the most salient city for this discussions, but Seattle is also growing because San Francisco’s land-use politics are even worse than Seattle’s. While Seattle has been bad, San Francisco has been (and is) far worse. By some measures San Francisco is now the most expensive place in the country to live. For many Silicon Valley tech workers who drive San Francisco housing prices, moving to Seattle immediately increases real income enormously through the one-two punch of (relatively) lower housing prices and no income tax. Seattle is still a steal relative to San Francisco and still has many of the amenities tech nerds like. So Seattle is catching much of San Francisco’s spillover, for good reason, and in turn places like Houston and Austin are catching much of Seattle’s spillover.

See also this discussion and my discussion of Jane Jacobs and urban land politics. Ignore comments that don’t cite actual research.

Furthermore, as Matt Yglesias points out in The Rent Is Too Damn High: What To Do About It, And Why It Matters More Than You Think, nominally free-market conservatives also tend to oppose development and support extensive land-use controls. But urban cities like Seattle almost always tilt leftward relative to suburbs and rural areas. Why this happens isn’t well understood.

Overall, it’s telling that Seattlites generate a lot of rhetoric around affordable housing and being progressive while simultaneously attacking policies that would actually provide affordable housing and be actually progressive. Some of you may have heard the hot air around Piketty and his book Capital in the 21st Century. But it turns out that, if you properly account for housing and land-use controls, a surprisingly large amount of the supposed disparity between top earners and everyone else goes away. The somewhat dubious obsession that progressives have with wealth concentration is tied up with the other progressive policy of preventing normal housing development!

This is a problem that’s more serious than it looks because parochial land-use controls affect the environment (in the sense of global climate change and resource consumption), as well as the innovation environment (close proximity increases innovation). Let’s talk first about the environment. Sunbelt cities like Phoenix, Houston, Dallas, and Atlanta have minimal mass transit, few mid- and high-rise buildings, and lots and lots of far-flung sub-divisions with cars. This isn’t good for the amount of carbon in the atmosphere, or for the amount of driving that people have to do, but warped land-use controls have given them to us anyway, and the easiest way to get around those land-use controls is to move to the periphery of an urban area and build there. Instead of super energy efficient mid-rises in Seattle, we get fifty tract houses in Dallas.

Then there’s the innovation issue. The more general term for this is “economic geography,” and the striking thing is how industries seem to cluster more in the Internet age. It is not equally easy to start a startup anywhere; they seem to occur in major cities. It isn’t even equally easy to be, say, a rapper: Atlanta produces a way disproportionate number of rappers (See also here). California’s San Fernando Valley appears to be where anyone who does porn professional wants to go. New York still attracts writers, though now they’re exiled to distant parts of the boroughs. My own novels say, “Jake Seliger grew up near Seattle and lives in New York City” (though admittedly I haven’t found much of a literary community here, which is probably my own fault). And so on, for numerous industries, most of them too small to have made a blip on my radar.

These issues interest me both as an intellectual matter and because they play into my work as a grant writer. Many of the ills grant-funded programs are supposed to solve, like poverty and homelessness, are dramatically worsened by persistent, parochial local land-use policies. Few of the superficial progressives in places like Seattle connect land-use policies to larger progressive issues.

So we get large swaths of people priced out of those lucrative job markets altogether, which (most) progressives dislike in theory. Nominal progressives become extreme reactionaries in their own backyards, which ought to tell us something important about them. Still, grant-funded programs that are supposed to boost income and have other positive effects on people’s lives are fighting against the tide . Fighting the tide is at best exceedingly difficult and at worst impossible. I don’t like to think that I’m fighting futile battles or doing futile work, and I consider this post part of the education process.

Few readers have gotten this far, and if you have, congratulations! The essence of the issue is simple supply and demand, but one sees a lot of misunderstanding and misinformation in discussions of it.

In addition, I don’t expect to have much of an impact. Earlier in this essay I mentioned Joseph Heath’s Enlightenment 2.0: Restoring sanity to our politics, our economy, and our lives, and in that book he observes that rationalists tend to get drown out by immediate, emotional responses. In this essay I’m arguing from a position of deliberate reason, while emotional appeals tend to “win” most intuitive arguments.

By the way: In Seattle itself, as of 2015 about two-thirds of Seattle’s land mass is reserved for single-family, detached houses. That’s insane in almost any city, but it’s especially insane in a major global city. Much of Seattle’s affordability problem could be solved or ameliorated by something as simple as legalizing houses with adjoining walls and no setback requirements. The housing that many people would love is literally illegal to build.

Finally, one commonly hears some objections to any sort of change in cities:

* “It’s ugly / out of character for the neighborhood:” As “How Tasteless Suburbs Become Beloved Urban Neighborhoods” explains, it takes about 50 years for design trends to go from “ugly” or “tacky” to “historic.” It’s hard to rebut people saying “that is ugly!” except by saying “no it isn’t!”, but one can see that most new developments are initially seen as undesirable and are eventually seen as normal. “Character” arguments, when made by owners, are usually code for “Protect my property investment.” It’s also not possible to protect the “character” of neighborhoods.

* “Foreigners and their money are buying everything up and making them more expensive:” Actually, real estate is, properly considered, an incredible export:

The key is to let more development happen in the in-demand, centrally located areas where the economic benefits are largest and the ecological costs the smallest, not just “transitional” neighborhoods and the exurban fringe. Take the existing stacks of apartments for rich people and replace them with taller stacks. Then watch the money roll in.

* “Gentrification is unfair:” Oddly, cities began to freeze in earnest, via zoning laws, in the 1970s. One can see this both from the link and from Google’s Ngram viewer, which sees virtually no references to gentrification until the late 70s, and the term really takes off later than that.

If gentrification is unfair—and maybe it is—the only real solution is to build as much housing as people want to consume, which will lower real prices towards the cost of construction. Few contemporary cities pursue this strategy, though. No other strategy will work.

EDIT: See also “How Seattle Killed Micro-Housing: One bad policy at a time, Seattle outlawed a smart, affordable housing option for thousands of its residents.” The city’s devotion to exclusionary housing policies is amazing. It’s not as bad as San Francisco, but compared to Texas it’s quite terrible.

* I’m reading “Millennials” as referring to people under age 30 who have no special status or insider connections. Few will have access to paid-off or rent-controlled housing in superstar cities. They’ll be clawing their way from the bottom without handouts. In cities like New York and San Francisco, a few older people have voted themselves into free stuff in the form of rent control. Most Millennials won’t have that.

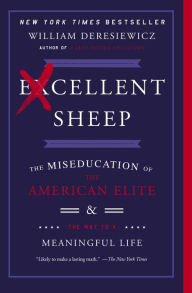

But Excellent Sheep is comprehensive, despite its overreach. But major orators know that if they have the audience the audience will forgive much, as such is the case here. The book is situated as one that fills a need and one that speaks to the author’s earlier self:

But Excellent Sheep is comprehensive, despite its overreach. But major orators know that if they have the audience the audience will forgive much, as such is the case here. The book is situated as one that fills a need and one that speaks to the author’s earlier self: