(Note: The original review is below, but I’m adding this addendum because I’ve started using the Kinesis Advantage as my primary keyboard. Regular keyboards now feel cramped and uncomfortable for extended use, and although my review is mostly positive, over time the Advantage has received the greatest accolade of all: it’s the keyboard I prefer to use.)

Two kinds of people are likely to want the Kinesis Advantage Keyboard: efficiency freaks and repetitive stress injury (RSI) sufferers. The Advantage is an unusual beast that promises a better keyboarding experience than conventional, flat keyboards. Does it? I firmly answer maybe, although enough people swear by them to make me think that, if nothing else, those with wrist pain or repetitive stress injuries benefit from the placebo effect if nothing else. There are two major barriers to using the keyboard: the first is retraining, which can be overcome relatively quickly. The second is the $300 retail price.

Still, once one adapts, typing becomes fun, like learning a secret. The Advantage’s curves remind one of advanced spaceship controls from a science fiction movie, as this manufacturer-provided picture demonstrates:

The Advantage.

Initial impressions and adjustments

I learned to touch type in sixth grade using Mavis Beacon teaches typing and remember the many frustrating hours spent struggling to learn while knowing that process would pay off. The Advantage makes you a beginner again, although learning was considerably easier than last time and the user’s manual wisely states that “Many new users of Kinesis contoured keyboards believe it will be difficult to adapt.”

It’s not hard, but it will take at least an hour of practice before you become proficient enough to use the keyboard regularly. For the first few days, my words per minute dropped precipitously. Yet I also discovered new things about the way I type, like that I tend to use my left index finger to hit “c.” This is a major problem on the Kinesis advantage because it’s virtually impossible to touch type and still use the index finger for that key. Even now, about half the time I come to a word with “c” in it, I get a “v,” instead; in this sentence, for example, I first wrote “vome.” A friend who tried the Kinesis didn’t have that problem, however, so it’s probably an issue unique to me.

The instincts of so many years of typing on standard keyboards are not broken in a week. This isn’t surprising given how long they’ve been ingrained. But an evening of steady practice was enough to become more or less proficient in everything except the aforementioned “c” key, which is located in a deep well where I couldn’t reach until I developed the necessary muscle memory through practice. By the start of week two, however, I was quite fast. Now I write this on my usual Unicomp Customizer and my hands feel strangely cramped, as if my fingers are constantly running into one another and I’m forced to use too small a space. This might simply show the power of adaptation and familiarity—themes I’ll return to later.

One nice feature of the Advantage is obvious from the start: Macs are first-class citizens out of the box, and no keyboard remapping is needed. As described below, a properly labeled command key is even included.

Ergonomics

The Advantage forces you to have better ergonomic posture; it’s hard at first, then it gets easier as time goes on. One’s forearms are almost forced to rest on the arm’s of a well-adjusted chair. One’s hands are spread wide, and the thumbs don’t arch as they naturally do on a standard regular keyboard. The thumbs are also used for a wider array of tasks, since the backspace, enter, and regular space characters are also driven by the thumbs. This distributes the keyboard load across one’s fingers.

The major downside of this “spread” keyboard design is that I found it difficult to reach some keys, including page up, page down, hyphen, and equals. Perhaps not coincidentally, they’re also keys I use more rarely than major keys, so I might simply have needed more time. Some key combinations, like the one for an em-dash, were a major pain at first. This is especially surprising because I’m a tall person with relatively big hands; women with small hands might find reaching some keys more difficult than me.

I also found it easier to sit with a straight back while using the Advantage. This might have been easier for me because I use a Humanscale keyboard tray that’s infinitely adjustable within about a six inch range, making finding the right level for the keyboard easy.

Tactile feel

As discussed in my post on More words of advice for the writer of a negative review, it’s hard to disentangle familiarity from genuine superiority; for example, some of Malcolm Gladwell’s work regarding the initial reaction to the Herman Miller Aeron Chair and the well-known negative response to Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring are reactions to things that are novel rather than bad. That being said, I still prefer the buckling springs that give the Unicomp Customizer and IBM Model Ms their bounce and unique feel.

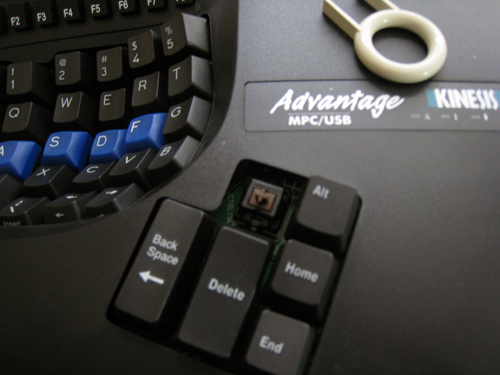

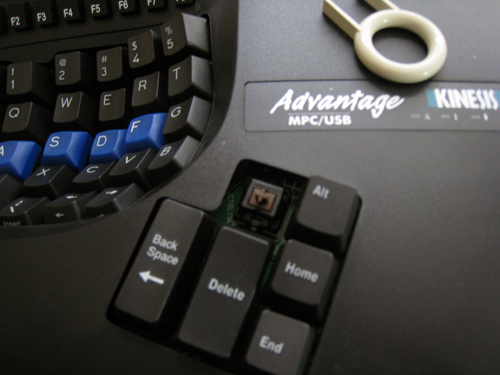

Still, the Kinesis uses very nice Cherry MX Brown keyboard switches, which offer tactile feel superior to cheap keyboards that use rubber dome switches (the linked article explains more about what this means):

The tool used to remove keycaps is at the upper right; putting Mac-labeled keys on was easy.

(Notice too the plastic device on the keyboard: that’s a key swapper included in the package, which allows one to immediately put a “command” key appropriate for Macs on the board. That’s a considerable improvement over Unicomp, which requires that one call to receive the appropriate caps.)

The Cherry switches are also considerably quieter than buckling springs, making the Advantage usable in group working environments. Attempting to use a Customizer for extended periods of time with others in the room probably won’t result in those others using the keyboard to forcefully silence its owner.

Overall, the Advantage has excellent keys.

Warning for programmers

In the default configuration, the brackets—[ and ]— and curly brackets—{ and }—are located in difficult-to-reach spots on the lower right side of the keyboard, necessitating a long stretch of the fingers. As such, almost anyone who does a fair amount of coding will want to remap the keyboard to make those keys easier to reach.

Durability

In the weeks I used mine, I saw no change in the keyboard. Although it’s made of plastic and not nearly as heavy as the Customizer, the Advantage feels sturdier than most original equipment manufacturer (OEM) keyboards. If any readers have used an Advantage for an extended period of time and would like to leave comments about their long-term durability, please do so.

Do repetitive stress injuries from keyboard usage actually exist? …

In a discussion about an article called “The World’s Greatest Keyboard,” some posters at Hacker News cited impressive evidence against RSI as being real; for example, one linked to John Sarno’s The Mind-Body Prescription, including this document summarizing his work. Another poster said that “There was a majority physical component [to his RSI problems] — actually using the mouse was much, much more painful — but there was also a psychological component. I suspect that this was anticipatory tension or somesuch, similar to a flinch response.” Another poster cited this series of posts about curing himself of RSI problems through psychology modification. There were also recommendations for this Trigger Point Therapy Workbook.

Given that testimony, as well as those who say the Advantage alleviated their pain problems, I’m not sure what to believe. I recall reading about studies that have found improved productivity among office workers when researchers increased or decreased lighting, or when researchers raise or lower temperatures. The theory is that workers aren’t necessarily more productive in higher or lower temperatures, but rather that they subconsciously respond to changes that show management is paying attention to them. By the same token, people with RSI problems might respond to keyboards like the Kinesis Advantage chiefly because they think that it will help them and because they have read accounts like the ones on Hacker News that claim improvement. This isn’t necessarily a bad thing: just because something happens in your head thanks to belief doesn’t mean it isn’t real.

… And assuming RSI injuries exist, will the Advantage fix them?

The existing research on the Kinesis Advantage is positive, but I’m not sure that any of the study designs I’ve found eliminate the placebo effect. For example, An evaluation of the ergonomics of three computer keyboards (2000) finds that “fixed” designs” like the Microsoft contoured keyboard “promoted a more natural hand position.” But the conclusion states that “the FIXED design has the potential to improve hand posture and thereby reduce the risk of developing cumulative trauma disorders of the wrist due to keyboard use.” Right. But does it actually improve such disorders? Tough call.

Another study, An ergonomic evaluation of the Kinesis ergonomic computer keyboard, found that:

Electromyographic data analysis showed that the resting posture on the Kinesis Ergonomic Computer Keyboard required significantly less activity to maintain than the resting posture on the standard keyboard for the flexor carpi ulnaris and the flexor digitorum sublimis. Furthermore, the Kinesis Ergonomic Computer Keyboard reduced the muscular activity required for typing in the flexor carpi ulnaris, the extensor digitorum communis. and the flexor digitorum sublimis.

Just because the Kinesis keyboards reduce stress on some body parts doesn’t necessarily mean you’ll automatically see a reduction in RSI issues. Both studies also come from the journal Ergonomics, which is still publishing, they appear to be reputable.

Another study, An assessment of alternate keyboards using finger motion, wrist motion and tendon travel (2000) is much more limited in scope and finds that Kinesis-style designs reduce tendon travel. But the “so what?” factor applies here too. “An assessment of alternate keyboards,” however, does not gender differences in the tendon travel, which is of interest because I still wonder if people with small hands would find it harder to type on the Advantage—perhaps the greater male tendon travel makes reaching unusual keys easier.

These studies do show, however, genuine differences in the physiology of keyboard usage. Consequently, people suffering from RSI issues should try the Advantage if they can afford it.

A word on price and productivity

No review can fail to mention the $300 price for an advantage. That’s obviously a lot of cash relative even to other high-quality keyboards. But compare the price of the keyboard to other good equipment: an Aeron chair is usually over $800, and a computer/monitor combo can still cost thousands. Relative to those kinds of price, the keyboard isn’t that expensive; as Dan Ariely demonstrates in Predictably Irrational, what we think of as a “reasonable” price very much depends on the anchors to which we compare. With anchor prices of $10 – $20 lousy rubber dome keyboards from major office supply chains as our point of comparison, we’re anchored to the wrong point.

A keyboard like an advantage or Customizer can easily make up for loss productivity if people are suffering from RSI injuries. A top programmer, consultant or lawyer might be worth hundreds of dollars an hour; not being able to work optimally because of keyboard design could cost vastly more than the keyboard itself and the retraining time necessary. Lisp hacker Bill Clementson raves about his Advantage, for example.

The treatment alternatives for RSI, like physical therapy, are also expensive, and far more expensive in both time and money terms than $300. For such people, the Advantage isn’t just cheaper in dollar terms—it could practically be a bargain.

In the introduction, I mentioned that efficiency freaks might find the Advantage faster because might be possible to type faster on an Advantage than on a traditional keyboard. Unfortunately, I can’t gauge whether this is true based on my experiences so far: by the end of the review period, I still typed slower than I had previously. Mistakes are a large part of my present slowness, especially when I’m hitting arrow keys along with backspace and/or return. Typing speed usually isn’t that important to me, however: I already type in the 50 word per minute range but think considerably slower. The track might let a train go 200 miles per hour, but if the train only goes 40, who needs the quality tracks?

That being said, if I were able to type for longer periods of time without hand fatigue, or if I were able to type with consistently fewer errors than I would on a normal keyboard, the price of an Advantage would quickly become irrelevant. But just learning whether that’s possible would take far longer than a few weeks.

Final thoughts

Despite its name, the Advantage is clearly going to be a minority taste. It’s hard to imagine many people choosing it unless they’re already experiencing fairly serious carpal tunnel or other problems. Although one can begin to touch type relatively quickly, even after a few weeks sometimes hit the arrow keys when I mean to hit letters on the bottom left of the keyboard, or vice-versa. The length of time necessary to become a fast typist again means that most will never try to make the investment because it probably won’t be worthwhile for them.

Still, enough people find the Advantage of value to keep Kinesis in business: the user manual says that Kinesis keyboards have been used commercially since 1992. In addition, the back of the Advantage says it was assembled in the United States, which is an impressive feat even among expensive products. If I did suffer from RSI problems, I would certainly try a Kinesis Advantage, although I might buy it from eBay rather than directly from a store: as of this writing, a few are available, all for less than $200. If you use a keyboard for eight hours a day almost every day, the price of retraining becomes incidental relative to the importance of being able to work comfortably.

The ultimate test of a keyboard is whether one chooses to use it on a day-to-day basis. In my case, I’m going back to the Customizer for the time being. But if I had the $300 handy, I’d probably be ordering one to see what happens after a couple months, rather than weeks, of usage. The promise of greater efficiency is a strong lure for me, but not strong enough to part me from the Customizer.

Yet.

EDIT: I wrote a long post on what I think of the the Kinesis Advantage, Unicomp Space Saver, and Das Keyboard two years later.

EDIT 2: There’s a worthwhile Hacker News discussion into the Advantage, among other things; sometimes HN will generate thousands of visitors who leave virtually no comments, because they comment on HN itself. Anyway, the top two comments say the Kinesis Advantage is quite durable, and both report that they’ve keyboards for more than ten years. One says Kinesis will repair keyboards that have been caught “drinking” soda. Taken together, they allay the longevity worry, especially if Kinesis offers service. It would be a major bummer to have to re-buy a $300 keyboard every five years because it broke, but it sounds like $300 also buys you high-quality keys that can take a lot of clacking.

EDIT 3: As of May 2014, I’m still using the Kinesis Advantage I bought in 2009. I did clean the entire board a couple months ago. I can still use normal keyboards but prefer not to. By far the most interesting recent keyboard release is the CODE Keyboard, which uses much quieter switches than the IBM Model-M-style keyboards. I have one that I use for business-related phone calls. In order of preference I like:

1. The Kinesis Advantage;

2. The Unicomp Ultra Classic (this one is too loud to use when others are around, and I’ll also note that Unicomp re-named the board I originally reviewed);

3. The CODE Keyboard (which is quiet while still being very good).

Note: The review unit was provided by Kinesis and returned to the manufacturer after this review was written.