As the title asks, why hasn’t someone tried to build or fund a very low-cost, very high-quality college? Or, if they have, what school is out there and has tried this?

It seems like a ripe strategy because virtually every (even slightly) selective school is pursing the same prestige strategy—high sticker prices, nominal discounts via “scholarships,” tenure-based faculty selection system, extensive administrative bloat, and so on. Yet even as schools relentlessly copy each other, news about outrageous student loan burdens is everywhere and probably affecting the choices made by students, and student openness to alternatives. At the same time, college tuition has been outpacing inflation for decades, and everyone knows it. Education is a component of the “cost disease” that is afflicting other sectors too. The number of college administrators has grown enormously (though that may not be the prime factor behind public-school cost increases). Students used to be possible to work summer jobs and graduate with little or no debt; schools in the 1960s or 1970s don’t appear to have been dramatically worse at education than schools today, and in some ways they may have been better, yet today colleges are many times more expensive. Schools trumpet their commitment to nominal education quality, the same way airlines trumpeted their commitment to passenger comfort, before deregulation forced airlines to compete on price and other metrics too, and anyone who’s been to a modern college knows that real commitment is “quality” is more rhetorical than real.

College costs and debts have soared, and at the same time the number of PhDs granted far outstrips the number of tenure-track or teaching jobs, so the workforce is available. Most universities and even many colleges care far more about research, much of which is bogus anyway, than teaching. Many universities don’t care about teaching at all, as long as the professor shows up to lecture, isn’t drunk, and doesn’t trade sex for grades. I hear many, many grad students and early professors lament the way their schools don’t care about teaching. There’s a surplus of cheap PhDs out there who’d desperately like to be professors. While professors who only teach two or three classes per semester complain relentlessly about all the “work” they supposedly have and how “busy” they allegedly are, it could be very easy to get professors to teach far more than they currently do at most schools, further reducing costs.

In short, the supply of faculty is there, and the supply of students ought to be there. With the setup above, let me repeat: why hasn’t anyone attempted to start a teaching-focused college with low tuition and extremely high-quality academics? I’m thinking of a school with a mandate to minimize the number of administrators, sports teams, and other boondoggles. One could even eliminate tenure, and thus ensure that PhDs hired today won’t still be on the payroll in 40 years. The school could highlight “proof of knowledge” over seat time as a metric; to my knowledge, there’s nothing intrinsic about four or five years of seat time. Students who study hard could and should spend less time in the seat.

Some of the situation I’m describing sounds like a community college, but I’m imagining a school that still draws from a national applicant pool and still maintains or attempts to maintain an elite or comprehensive academic character. Think of a liberal arts school but scaled up and with fewer administrators. If I were a billionaire I might try to do this; stupendously rich people loved endowing schools in the 19th Century, but that seems to have fallen out of fashion. Still, it worked then, so perhaps it could work now.

It may be that schools are really selling prestige and status, and consequently a low-cost, high-quality teaching school would be too low prestige and low status to attract students.

Still, and again as noted previously, pretty much every school, public or private, is pursuing the exact same prestige, admissions, and marketing strategy. With one or two exceptions (CalTech, University of Chicago—okay, there are a few others, but not many), they don’t even try (really or seriously) to distinguish themselves, and almost every school competes for the same BS college rankings. Such a uniform market seems ripe for alternate approaches, yet none are being tried or have taken off, though there are some small scale efforts, like Minerva.

What am I missing?

* Maybe it was easier to start colleges in the 19th Century, when regulation was nonexistent and complex subsidies of various kinds weren’t available. In the 19th Century, many colleges were also founded with the explicit intent of saving students’ souls, so perhaps the lack of religiosity in today’s billionaires and/or most of today’s students is a factor. God is an underappreciated component of many older endeavors.

* Current schools might just be too damn good at marketing for others to break in. Plus, college is a huge investment, which engenders a certain amount of conservatism in choices. Given costs, though, I think there’s room for experimentation here.

* Maybe there are efforts afoot and they’ve either failed or are too small for me to have noticed.

* Current schools are pursuing a complex price discrimination strategy, in which the sticker price is paid by a relatively small number of students, and much of the study body receives “scholarships” that are really tuition discounts. Maybe this system is more appealing to students and possibly schools than a transparent, everyone-pays-$5,000-per-year strategy.

* Students by and large pay with their parents’ money or pay with loans, so many an unbundled version of a school really is less attractive than one with lots of administrators, feel-good projects, fancy gyms, etc. Despite schools’ rhetoric to the contrary, they’re obsessed with attracting and retaining rich kids, so that market may be where all the juice is.

* Billionaires who might fund this are busy doing other things.

* The number of “good” or at least weird and different students who would try such a school is not great enough (given the current cost of college and the number of students out there, I find this one hard to believe, but it isn’t impossible).

I’m guessing number four is most likely, but maybe there are other features I’m missing.

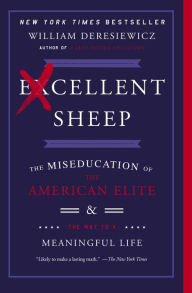

But Excellent Sheep is comprehensive, despite its overreach. But major orators know that if they have the audience the audience will forgive much, as such is the case here. The book is situated as one that fills a need and one that speaks to the author’s earlier self:

But Excellent Sheep is comprehensive, despite its overreach. But major orators know that if they have the audience the audience will forgive much, as such is the case here. The book is situated as one that fills a need and one that speaks to the author’s earlier self: