Becoming Freud could be called “Reading Freud” or “Defending Freud,” because it has little to do with how Freud became Freud—there are decent, let alone good, answers to this question—and much to do with other matters, worthy in their own regard. The story—it is only tenuously a biography—is consistently elegant, though not in a flashy way; Philips reminds me of Louis Menand and the better New Yorker writers in general in this regard. Consider this: “Freud developed psychoanalysis, in his later years, by describing how it didn’t work; clinically, his failures were often more revealing to him than his successes.” Twelve words before the semicolon are balanced by eleven after, and the paradox of failure being more “revealing” than success is unexpected and yet feels right. As the same passage shows, Becoming Freud is also pleasantly undogmatic, unlike many modern-day Freudians, or people who claim Freud’s mantle or cite his work. I ran into some of those people in academia, and the experience was rarely positive on an intellectual level. Some were lovely people, though.

It is hard to get around how much Freud was wrong about, yet Philips manages this deftly by interpreting him interpreting others, rather than on his conceivably disprovable claims. Freud in this reading is literary. In Becoming Freud we get sentences like:

It is hard to get around how much Freud was wrong about, yet Philips manages this deftly by interpreting him interpreting others, rather than on his conceivably disprovable claims. Freud in this reading is literary. In Becoming Freud we get sentences like:

Freud’s work shows us not merely that nothing in our lives is self-evident, that not even the facts of our lives speak for themselves; but that facts themselves look different from a psychoanalytic point of view.

But this sounds like a description of language or of literary interpretation, rather than the final statement on the relation of facts to the mind.Plus, I’m not sure facts are all that different—but I sense that Philips would argue that’s because of Freud’s influence. Philips further tells us that “We spend our lives, Freud will tell us in his always lucid prose, not facing the facts, the facts of our history, in all their complication; above all the facts of our childhood.”

In short, Becoming Freud is closer to literary interpretation than to biography, much as Freud was closer to a literary critic than a psychologist. I’m not the first to notice that he writes of patients more like characters than like people. Philips reminds us that Freud’s “writing is studded with references to great men—Plato, Moses, Hannibal, Michelangelo, Leonardo da Vinci, Goethe, Shakespeare, among others—most of them artists; and all of them, in Freud’s account, men who defined their moment, not men struggling to assimilate to their societies. . .” These passages also, I think, show the book’s interpretative strengths and its sometimes exhausting qualities.

There is no real summing of Freud’s influence, when remains even when few will take his supposed science seriously. Yet despite the unseriousness of the science, talking therapy is still with us. The word “despite” seems appropriate in discussions of Freud: Despite the dubious effectiveness of talking therapy it remains in widespread use because we don’t have good alternatives. Many of us are socially isolated and lack friends; Bowling Alonew is prescient and TV and Facebook are not good substitutes for coffee or 3 a.m. phone calls. For centuries the West has valorized individual freedom and attempted to vaporize community bonds. We may be victims of our own success in this respect, and we’re now tasked with building communities based primarily on common interests. In therapeutic terms, we use the tools we have not because they are good but because they are better than nothing. Freud is in contemporary respects not good but he did articulate some of the ideas that would define the 20th Century. Getting a couple of major peaks is often more important than consistently being minorly right. I may be more inclined temperamentally towards the latter.

Sentences like this abound: “In this period of Freud’s life—as in any period in anyone’s life—the discrepancy between the documented and the undocumented life is striking, and can only be imagined.” Yet such issues sort of defeat the purpose of biography, no? It may also be why novelists like writing the lives of famous people: one gets to imagine their inner and outer selves without the pesky need for proof.

Philips’s Freud is an idealized person and for that reason I like this Freud better than most writers’s Freud. As Philips points out repeatedly the book is inadequate as a biography; he says all biographies are, which may be true to some extent, but the fewer the facts the less adequate the interpretations that might be drawn from them. Becoming Freud is similar to Alain de Botton’s Kiss & Tell, though Botton’s book is a novel. Here is The New Yorker’s take. There is a novel in there somewhere. We don’t know and likely can never know Freud. Few modern writers have such privilege, unless maybe they delete their entire email histories before they die.

There is not enough known about Freud to even make his biography feel novelistic. Whether this is good or bad depends on the reader.

It is hard to get around how much Freud was wrong about, yet Philips manages this deftly by interpreting him interpreting others, rather than on his conceivably disprovable claims. Freud in this reading is literary. In Becoming Freud we get sentences like:

It is hard to get around how much Freud was wrong about, yet Philips manages this deftly by interpreting him interpreting others, rather than on his conceivably disprovable claims. Freud in this reading is literary. In Becoming Freud we get sentences like:

When I first bought a Unicomp Ultra Classic I was in college and a couple tiny companies made mechanical keyboards, including Unicomp and Matias (whose early products were

When I first bought a Unicomp Ultra Classic I was in college and a couple tiny companies made mechanical keyboards, including Unicomp and Matias (whose early products were  But the real news is no news: a bunch of keyboards exist and they’re all pretty good. The word “slight” appears three times in the first two paragraphs because there aren’t clear winners. If you type a lot and aren’t interested in the minutia, get a CODE Keyboard and put the rest out of your mind. If you want a more ergonomic experience and have the cash, get a Kinesis Advantage and learn how to use it (and be ready for weird looks from your friends when they see it). Options are beautiful but don’t let them drive you mad.

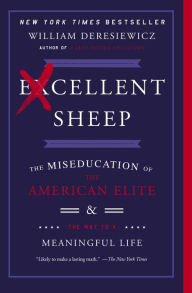

But the real news is no news: a bunch of keyboards exist and they’re all pretty good. The word “slight” appears three times in the first two paragraphs because there aren’t clear winners. If you type a lot and aren’t interested in the minutia, get a CODE Keyboard and put the rest out of your mind. If you want a more ergonomic experience and have the cash, get a Kinesis Advantage and learn how to use it (and be ready for weird looks from your friends when they see it). Options are beautiful but don’t let them drive you mad. But Excellent Sheep is comprehensive, despite its overreach. But major orators know that if they have the audience the audience will forgive much, as such is the case here. The book is situated as one that fills a need and one that speaks to the author’s earlier self:

But Excellent Sheep is comprehensive, despite its overreach. But major orators know that if they have the audience the audience will forgive much, as such is the case here. The book is situated as one that fills a need and one that speaks to the author’s earlier self: