If you find this piece worthwhile, consider the Go Fund Me that’s funding ongoing cancer care.

A story from Dan Luu, from back when he “TA’ed EE 202, a second year class on signals and systems at Purdue:”

When I suggested to the professor that he spend half an hour reviewing algebra for those students who never had the material covered cogently in high school, I was told in no uncertain terms that it would be a waste of time because some people just can’t hack it in engineering. I was told that I wouldn’t be so naive once the semester was done, because some people just can’t hack it in engineering.

This matches my experiences: when I was a first-year grad student in English,[1] my advisor was complaining about his students not knowing how to use commas, and I made a suggestion very similar to Luu’s: “Why not teach commas?” His reasoning was slightly different from “some people just can’t hack it in engineering,” in that he thought students should’ve learned comma usage in high school. I argued that, while he might be right in theory, if the students don’t know how to use commas, he ought to teach them how. He looked at me like I was a little dim and said “no.”

I thought and still think he’s wrong.

If a person doesn’t know fundamentals of a given field, and particularly if a larger group doesn’t, teach those fundamentals.[2] I’ve taught commas and semicolons to students almost every semester I’ve taught in college, and it’s neither time consuming nor hard. A lot of the students appreciate it and say no one has ever stopped to do so.

Usually I ask, when the first or second draft of their paper is due for peer editing, that students write down four major comma rules and a sample sentence showcasing each. I’m looking for something like: connecting two independent clauses (aka complete sentences) with a coordinating conjunction (like “and” or “or”), offsetting a dependent word, clause, or phase (“When John picked up the knife, …”), as a parenthetical (sometimes called “appositives” for reasons not obvious to me but probably having something to do with Latin), and lists. Students often know about lists (“John went to the store and bought mango, avocado, and shrimp”), but the other three elude them.

I don’t obsess with the way the rules are phrased and if the student has gotten the gist of the idea, that’s sufficient. They write for a few minutes, then I walk around and look at their answers and offer a bit of individual feedback. Ideally, I have some chocolate and give the winner or sometimes winners a treat. After, we go over the rules as a class. I repeat this three times, for each major paper. Students sometimes come up with funny example sentences. The goal is to rapidly learn and recall the material, then move on. There aren’t formal grades or punishments, but most students try in part because they know I’m coming around to read their answers.

We do semicolons, too—they’re used to conjoin related independent clauses without a coordinating conjunction, or to separate complex lists. I’ll use an example sentence of unrelated independent clauses like “I went to the grocery store; there is no god.”

I tell students that, once they know comma rules, they can break them, as I did in the previous paragraph. I don’t get into smaller, less important comma rules, which are covered by whatever book I assign students, like Write Right!.

Humanities classes almost never teach editing, either, which I find bizarre. I suspect that editing is to debugging as writing is to programming (or hardware design): essential. I usually teach editing at the sentence level, by collecting example sentences from student journals, then putting them on the board and asking students: “what would you do with this sentence, and why?” I walk around to read answers and offer brief feedback or tips. These are, to my mind, fundamental skills. Sentences I’ve used in the past include ones like this, regarding a chapter from Alain de Botton’s novel On Love: “Revealed in ‘Marxism,’ those who are satisfying a desire are not experiencing love rather they are using the concept to give themselves a purpose.” Or: “Contrast is something that most people find most intriguing.” These sentences are representative of the ones first- and second-year undergrads tend to produce at first.

I showed Bess an early version of this essay, and it turns out she had experiences similar to Luu’s, but at Arizona State University (ASU):

My O-chem professor was teaching us all something new, but he told me to quit when I didn’t just understand it immediately and was struggling. He had daily office hours, and I was determined to figure out the material, so I kept showing up. He wanted to appear helpful, but then acted resentful when I asked questions, “wasting his time” with topics from which he’d already moved on, and which I “should already understand”.

He suggested I drop the class, because “O-Chem is just too much for some people.” When I got the second-highest grade in the class two semesters in a row, he refused to write me a letter of recommendation because it had been so hard for me to initially grasp the material, despite the fact that I now thought fluently in it. My need for extra assistance to grasp the basics somehow overshadowed the fact that I became adept, and eventually offered tutoring for the course (where I hope I was kinder and more helpful to students than he was).

Regarding Bess’s organic chemistry story, I’m reminded of a section from David Epstein’s book Range: How Generalists Triumph in a Specialized World. In his chapter “Learning, Fast and Slow” Epstein writes that “for learning that is both durable (it sticks) and flexible (it can be applied broadly), fast and easy is precisely the problem” (85). Instead, it’s important to encounter “desirable difficulties,” or “obstacles that make learning more challenging, slower, and more frustrating in the short term, but better in the long term.” According to Epstein, students like Bess are often the ones who master the material and go on to be able to apply it. How many students has that professor foolishly discouraged? Has he ever read Range? Maybe he should.

Bess went on:

Dan’s story also reminds me of an attending doctor in my emergency medicine program; she judged residents on what they already knew and thought negatively of ones who, like me, asked a bunch of questions. But how else are you supposed to learn? This woman (I’m tempted to use a less-nice word) considered a good resident one who’d either already been taught the information during medical school, or, more likely, pretended to know it.

She saw the desire to learn and be taught—the point of a medical residency— as an inconvenience (hers) and a weakness (ours). Residency should be about gaining a firm foundation in an environment ostensibly about education, but turns out it’s really about cheap labor, posturing, and also some education where you can pick it up off the floor. When I see hospitals claiming that residency is about education, not work, I laugh. Everyone knows that argument is bullshit.

We can and should do a better job of teaching fundamentals, though I don’t see a lot of incentive to do so in formal settings. In most K – 12 public schools, after one to three years most teachers can’t effectively be fired, due to union rules, so the incentive to be good, let alone great, is weak. In universities, a lot of professors are, as I noted earlier, hired for research, not teaching. It’s possible that, as charter schools spread, we’ll see more experimentation and improvement at the ˚K –12 level. At the college and graduate school level, I’d love to see more efforts at instructional and institutional experimentation and diversity, but apart from the University of Austin, Minerva, the Thiel Fellowship, and a few other efforts, the teaching business is business-as-usual.

Moreover, there’s an important quirk of the college system: Congress and the Department of Education have outsourced the credentialing of colleges and universities to regional accreditation bodies. Harvard, for example, is accredited by “The New England Association of Schools and Colleges (NEASC).” But guess who makes up the regional accreditation bodies? Existing colleges and universities. How excited are existing colleges and universities to allow new competitors? Exactly. The term for this is “cartel.” This point is near top-of-mind because Marc Andreessen and Ben Horowitz emphasized it on their recent podcast regarding the crises of higher education. If you want a lot more, their podcast is good.

Unfortunately, my notions of what’s important in teaching don’t matter much any more because it’s unlikely I’ll ever teach again, given that I no longer have a tongue and am consequently difficult to understand. I really liked (and still like!) teaching, but doing it as an adjunct making $3 – $4k / class has been unwise for many years and is even more unwise given how short time is for me right now. Plus, the likelihood of me living out the year is not high.

In terms of trying to facilitate change and better practices, I also don’t know where, if at all, people teaching writing congregate online. Maybe they don’t congregate anywhere, so it’s hard to try and engage large numbers of instructors.

Tyler Cowen has a theory, expounded in various podcasts I’ve heard him on, that better teachers are really here to inspire students—which is true regarding both formal and informal education. Part of inspiration is, in my view, being able to rapidly traverse the knowledge space and figure out whatever the learner needs.

Until we perfect neural chips that can download the entirety of human knowledge to the fetal cortex while still in utero, no one springs from the womb knowing everything. In some areas you’ll always be a beginner. Competence, let alone mastery, starts with desire and basics.

If you’ve gotten this far, consider the Go Fund Me that’s funding ongoing care.

- Earlier reading: “Most people don’t read carefully or for comprehension,” another response to Dan Luu.

[1] Going to grad school in general is a bad idea; going in any humanities discipline is a horribly bad idea, but I did it, and am now a cautionary tale for having done it.

[2] Schools like Purdue also overwhelmingly select faculty on the basis of research and grantsmanship, not teaching, so it’s possible that the instructors don’t care at all. Not every researcher is a Feynman, to put it lightly.

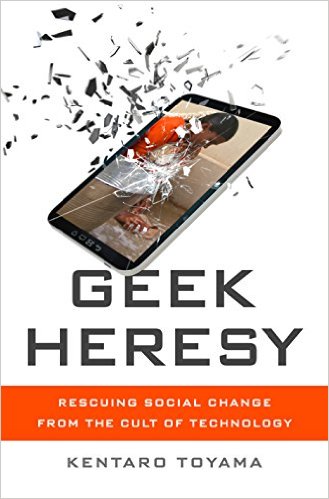

There are many other fascinating points—too many to describe all of them here. To take one, it’s often hard to balance short- and long-term wants. Many people want to write a novel but don’t want to write right now. Over time, that means the novel never gets written, because novels get written one sentence and one day at a time. Technology does not resolve this challenge. If anything, Internet access may make it worse. Many of us have faced an important long-term project only to diddle around on websites:

There are many other fascinating points—too many to describe all of them here. To take one, it’s often hard to balance short- and long-term wants. Many people want to write a novel but don’t want to write right now. Over time, that means the novel never gets written, because novels get written one sentence and one day at a time. Technology does not resolve this challenge. If anything, Internet access may make it worse. Many of us have faced an important long-term project only to diddle around on websites: