At The Complete Review, Michael Orthofer writes of John Updike that

Dead authors do tend to fade fast these days — sometimes to be resurrected after a decent interval has passed, sometimes not –, which would seem to me to explain a lot. As to ‘the American literary mainstream’, I have far too little familiarity with it; indeed, I’d be hard pressed to guess what/who qualifies as that.

Orthofer is responding to a critical essay that says: “Much of American literature is now written in the spurious confessional style of an Alcoholics Anonymous meeting. Readers value authenticity over coherence; they don’t value conventional beauty at all.” I’m never really sure what “authenticity” and its cousin “relatability” mean, and I have an unfortunate suspicion that both reference some lack of imagination in the speaker; still, regarding the former, I find The Authenticity Hoax: How We Get Lost Finding Ourselves persuasive.

But I think Orthofer and the article are subtly pointing towards another idea: literary culture itself is mostly dead. I lived through its final throes—perhaps like someone who, living through the 1950s, saw the end of religious Christianity as a dominant culture, since it was essentially gone by the 1970s—though many claimed its legacy for years after the real thing had passed. What killed literary culture? The Internet is the most obvious, salient answer, and in particular the dominance of social media, which is in effect its own genre—and, frequently, its own genre of fiction. Almost everyone will admit that their own social media profiles attempt to showcase a version of their best or ideal selves, and, thinking of just about everyone I know well, or even slightly well, the gap between who they really are and what they are really doing, and what appears on their social media, is so wide as to qualify as fiction. Determining the “real” self is probably impossible, but determining the fake selves is easier, and the fake is everywhere. Read much social media as fiction and performance and it will make more sense.

Everyone knows this, but admitting it is rarer. Think of all the social media photos of a person ostensibly alone—admiring the beach, reading, sunbathing, whatever—but the photographer is somewhere. A simple example, maybe, but also one without the political baggage of many other possible examples.

Much of what passes for social media discourse makes little or no sense, until one considers that most assertions are assertions of identity, not of factual or true statements, and many social media users are constructing a quasi-fictional universe not unlike the ones novels used to create. “QAnon” might be one easy modern example, albeit one that will probably go stale soon, if it’s not already stale; others will take its place. Many of these fictions are the work of group authors. Numerous assertions around gender and identity might be a left-wing-valenced version of the phenomenon, for readers who want balance, however spurious balance might be. Today, we’ve in some ways moved back to a world like that of the early novel and the early novelists, when “fact” and “fiction” were much more disputed, interwoven territories, and many novels claimed to be “true stories” on their cover pages. The average person has poor epistemic hygiene for most topics not directly tied to income and employment, but the average person has a very keen sense of tribe, belonging, and identity—so views that may be epistemically dubious nonetheless succeed if they promote belonging (consider also The Elephant in the Brain by Robin Hanson and Kevin Simler for a more thorough elaboration on these ideas). Before social media, did most people really belong, or did they silently suffer through the feeling of not belonging? Or was something else at play? I don’t know.

In literary culture terms, the academic and journalistic establishment that once formed the skeletal structure upholding literary culture has collapsed, while journalists and academics have become modern clerics, devoted more to spreading ideology than exploring the human condition, or to art, or to aesthetics. Academia has become more devoted to telling people what to think, than helping people learn how to think, and students are responding to that shift. Experiments like the Sokal Affair and its successors show as much. The cult of “peer review” and “research” fits poorly in the humanities, but they’ve been grafted on, and the graft is poor.

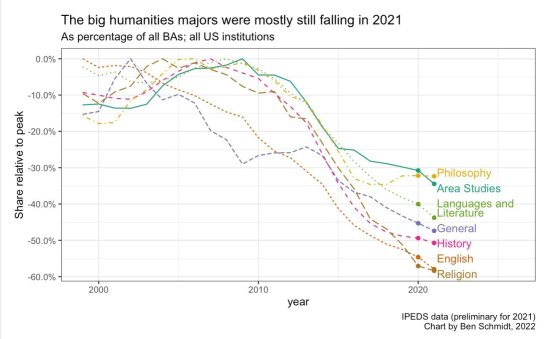

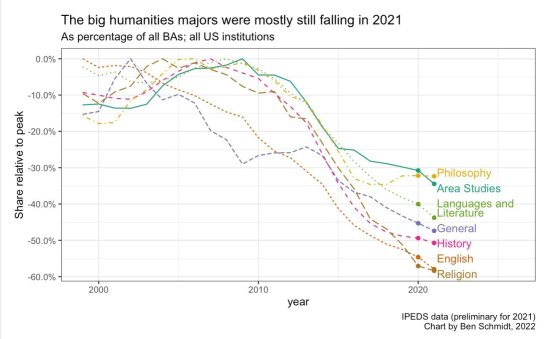

Strangely, many of the essays lamenting the fall of the humanities ignore the changes in the content of the humanities, in both schools and universities. The number of English majors in the U.S. has dropped by about 50% from 2000 to 2021:

History and most of other humanities majors obviously show similar declines. Meanwhile, the number of jobs in journalism has approximately halved since the year 2000; academic jobs in the humanities cratered in 2009, from an already low starting point, and have never recovered; even jobs teaching in high school humanities subjects have a much more ideological, rather than humanistic, cast than they did ten years ago. What’s taken the place of reading, if anything? Instagram, Snapchat, TikTok, and, above all, Twitter.

Twitter, in particular, seems to promote negative feedback and fear loops, in ways that media and other institutions haven’t yet figured out how to resist. The jobs that supported the thinkers, critics, starting-out novelists, and others, aren’t there. Whatever might have replaced them, like Twitter, isn’t equivalent. The Internet doesn’t just push most “content” (songs, books, and so forth) towards zero—it also changes what people do, including the people who used to make up what I’m calling literary culture or book culture. The costs of housing also makes teaching a non-viable job for a primary earner in many big cities and suburbs.

What power and vibrancy remains in book culture has shifted towards nonfiction—either narrative nonfiction, like Michael Lewis, or data-driven nonfiction, with too many examples to cite. It still sells (sales aren’t a perfect representation of artistic merit or cultural vibrancy, but they’re not nothing, either). Dead authors go fast today not solely or primarily because of their work, but because the literary culture is going away fast, if it’s not already gone. When John Updike was in his prime, millions of people read him (or they at last bought Couples and could spit out some light book chat about it on command). The number of writers working today who the educated public, broadly conceived of, might know about is small: maybe Elena Ferrante, Michel Houllebecq, Sally Rooney, and perhaps a few others (none of those three are American, I note). I can’t even think of a figure like Elmore Leonard: someone writing linguistically interesting, highly plotted material. Bulk genre writers are still out there, but none who I’m aware of who have any literary ambition.

See some evidence for the decline of literary cultures in the decline of book advances; the Authors Guild, for example, claims that “writing-related earnings by American authors [… fell] to historic lows to a median of $6,080 in 2017, down 42 percent from 2009.” The kinds of freelancing that used to exist has largely disappeared too, or become economically untenable. In If You Absolutely Must by Freddie deBoer, he warns would-be writers that “Book advances have collapsed.” Money isn’t everything but the collapse of already-shaking foundations of book writing is notable, and quantifiable. Publishers appear to survive and profit primarily off very long copyright terms; their “backlist” keeps the lights on. Publishers seem, like journalists and academics, to have become modern-day clerics, at least for the time being, as I noted above.

Consider a more vibrant universe for literary culture, as mentioned in passing here:

From 1960 to 1973, book sales climbed 70 percent, but between 1973 and 1979 they added less than another six percent, and declined in 1980. Meanwhile, global media conglomerates had consolidated the industry. What had been small publishers typically owned by the founders or their heirs were now subsidiaries of CBS, Gulf + Western (later Paramount), MCA, RCA, or Time, Inc. The new owners demanded growth, implementing novel management techniques. Editors had once been the uncontested suzerains of title acquisition. In the 1970s they watched their power wane.

A world in which book sales (and advances) are growing is very different from one of decline. It’s reasonable to respond that writing has rarely been a path to fame or fortune, but it’s also reasonable to note that, even against the literary world of 10 or 20 years ago, the current one is less remunerative and less culturally central. Writers find the path to making any substantial money from their writing harder, and more treacherous. Normal people lament that they can’t get around to finishing a book; they rarely lament that they can’t get around to scrolling Instagram (that’s a descriptive observation of change).

At Scholar’s Stage, Tanner Greer traces the decline of the big book and the big author:

the last poet whose opinion anybody cared about was probably Allen Ginsberg. The last novelist to make waves outside of literary circles was probably Tom Wolfe—and he made his name through nonfiction writing (something similar could be for several of other prominent essayists turned novelists of his generation, like James Baldwin and Joan Didion). Harold Bloom was the last literary critic known outside of his own field; Allan Bloom, the last with the power to cause national controversy. Lin-Manuel Miranda is the lone playwright to achieve celebrity in several decades.

I’d be a bit broader than Greer: someone like Gillian Flynn writing Gone Girl seemed to have some cultural impact, but even books like Gone Girl seem to have stopped appearing. The cultural discussion rarely if ever revolves around books any more. Publishing and the larger culture have stopped producing Stephen Kings. Publishers, oddly to my mind, no longer even seem to want to try producing popular books, preferring instead to pursue insular ideological projects. The most vital energy in writing has been routed to Substack.

I caught the tail end of a humane and human-focused literary culture that’s largely been succeeded by a political and moral-focused culture that I hesitate to call literary, even though it’s taken over what remains of those literary-type institutions. This change has also coincided with a lessening of interest in those institutions: very few people want to be clerics and scolds—many fewer than wonder about the human condition, though the ones who do want to be clerics and scolds form the intolerant minority in many institutions. Shifting from the one to the other seems like a net loss to me, but also a net loss that I’m personally unable to arrest or alter. If I had to pick a date range for this death, it’d probably be 2009 – 2015: the Great Recession eliminates many of the institutional jobs and professions that once existed, along with any plausible path into them for all but the luckiest, and by 2015 social media and scold culture had taken over. Culture is define but easy to feel as you exist within and around it. By 2010, Facebook had become truly mainstream, and everyone’s uncle and grandma weren’t just on the Internet for email and search engines, but for other people and their opinions.

Maybe mainstream literary culture has been replaced by some number of smaller micro-cultures, but those microcultures don’t add up to what used to be a macroculture.

In this essay, I write:

I’ve been annoying friends and acquaintances by asking, “How many books did you read in the last year?” Usually this is greeted with some suspicion or surprise. Why am I being ambushed? Then there are qualifications: “I’ve been really busy,” “It’s hard to find time to read,” “I used to read a lot.” I say I’m not judging them—this is true, I will emphasize—and am looking for an integer answer. Most often it’s something like one or two, followed by declamations of highbrow plans to Read More In the Future. A good and noble sentiment, like starting that diet. Then I ask, “How many of the people you know read more than a book or two a year?” Usually there’s some thinking, and rattling off of one or two names, followed by silence, as the person thinks through the people they know. “So, out of the few hundred people you might know well enough to know, Jack and Mary are the two people you know who read somewhat regularly?” They nod. “And that is why the publishing industry works poorly,” I say. In the before-times, anyone interested in a world greater than what’s available around them and on network TV had to read, most often books, which isn’t true any more and, barring some kind of catastrophe, probably won’t be true again.

Reading back over this I realize it has the tone and quality of a complaint, but it’s meant as a description, and complaining about cultural changes is about as effective as shaking one’s fist at the sky: I’m trying to look at what’s happening, not whine about it. Publishers go woke and see the sales of fiction fall and respond by doubling down, but I’m not in the publishing business and the intra-business signaling that goes on there. One could argue changes noted are for the better. Whining about aggregate behavior and choices has rarely, if ever, changed it. I don’t think literary culture will ever return, any more Latin, epic poetry, classical music, opera, or any number of other once-vital cultural products and systems will.

In some ways, we’re moving backwards, towards a cultural fictional universe with less clearly demarcated lines between “fact” and “fiction” (I remember being surprised, when I started teaching, by undergrads who didn’t know a novel or short stories are fiction, or who called nonfiction works “novels”). Every day, each of us is helping whatever comes next, become. The intertwined forces of technology and culture move primarily in a single direction. The desire for story will remain but the manifestation of that desire aren’t static. Articles like “Leisure reading in the U.S. is at an all-time low” appear routinely. It’s hard to have literary culture among a population that doesn’t read.

See also:

* What happened with Deconstruction? And why is there so much bad writing in academia?

* Postmodernisms: What does that mean?