Some things about the clinical trial process—and the behaviors of the drug companies, hospitals, and oncologists that are part of the clinical trial process—puzzle me, because I notice problems and common, suboptimal practices that seem easy to fix and yet, from what I’ve experienced and observed, they persist. That slows medicine and science, which is euphemistic way of saying: “more people die, sooner, than would by using better practices and processes.” Patient care and outcomes suffer. Hard-to-fix problems like the FDA aren’t readily solved because those fixes likely demand congressional action, and most congresspeople aren’t pressured to act by voters, and the potential voters most interested in FDA reform have probably already died, or are in the process of dying, and thus are unable to make it to their local polling place.*

“Puzzles about oncology and clinical trials” is a companion to “Please be dying, but not too quickly: A clinical trial story and three-part, very deep dive into the insanity that is the ‘modern’ clinical trial system. Buckle up.” The clinical trial system could be a lot worse, and many treatments obviously get through the system, but, in its current state, the clinical trial system far from optimal, to the point that I’d characterize it as “pretty decently broken.” Interestingly, too, almost all parties involved appear to acknowledge that it’s broken, but no one can seem to coordinate enough pieces to generate substantial improvement. While the clinical-trial field is being seduced by AI models and large-scale tech “solutions,” most of which don’t yet work, some of the problems I’ve noticed and am listing here could be, if not solved altogether, then at least substantially ameliorated at the level of the individual or department, rather than the level of states, the country as a whole, or the FDA:

1. Many oncologists don’t appear to know the clinical trial landscape, even in their sub-specialty. As you might’ve read in Bess’s “Please be dying, but not too quickly” essay / guide, almost none of the head and neck oncologists Bess and I talked to knew the head and neck clinical trial landscape well. Most barely seemed to know it at all, apart from vague reputation (“MD Anderson has a lot of trials” or “Try the University of Colorado” or “I’ve heard good things about Memorial-Sloan Kettering (MSK)”). A lot of that advice was helpful, and I don’t want to scorn it or the oncologists giving it, but that advice also wasn’t at the ideal resolution.

It’s puzzling that more oncologists don’t learn the clinical trial landscape, given how many patients must, like me, reach the end of conventional treatments and want or need to try whatever might be next. To a non-expert outsider, the trial landscape is a bizarre, confusing world that takes enormous time and effort to understand. But to an oncologist or someone else working in the field, it shouldn’t take more than a few hours once every month or two or even three to keep abreast of what’s happening.

In head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC), the ailment that’s killing me, there are a lot of trials, though most aren’t highly relevant and perhaps 30 – 50 “good” trials are recruiting at any given moment. The “good ones” mean ones in which a drug company is investing heavily in the drug and the drug is at least in phase 1b and more likely phase 2. Moreover, trials can last years, with varying periods of enrollment, so once an oncologist understands the “good” trials, those trials are likely to be relevant for years. Keeping up with the better trials, even via clinicaltrials.gov, shouldn’t consume lots of time. It took Bess an unbelievable amount of effort and energy to get up to speed from nothing, but the trial situation is like riding a bike: starting from a stop is much tougher than maintaining speed.

Bess spent 50+ hours a week for six straight weeks trying to learn the head and neck clinical landscape, and, with the help of a great consultant named Eileen Faucher, she basically did. Though Bess is a doctor, she’s not an oncologist and doesn’t have the baseline expertise that comes from treating head and neck cancer patients as a career. Bess doesn’t attend the yearly ASCO: head and neck conference where breakthroughs and the research landscape are discussed. Yet she, despite being in the emergency room, somehow became better versed in both the most promising experimental molecules and the up-to-date clinical trial offerings than any other single physician we spoke with (a few were well-informed, to be sure, and if you are well informed and gathering up your outrage, please release it!). The big picture wasn’t obvious at first, but it was discoverable to a determined, non-expert ER doc, and therefore it should be to experts.

Although I’m now in a trial hosted by UCSD’s Moores Cancer Center for a bispecific antibody called MCLA-158 / petosemtamab, Bess just reached out to her contacts at back-up trials, because I’m getting scans on Nov. 21, and those scans may show that petosemtamab is failing and we should try something else, instead of waiting to die. The rate of return for a few “how’s it looking?” e-mails or calls from Bess to trial coordinators and oncologists seems exceptionally high. In my view, community oncologists should do the same thing every couple months. UCSD has probably the best and most extensive program in the west. It would be easy for an oncologist like mine at the Mayo Clinic Phoenix, Dr. Savvides, to send an email every three or four months that says: “Any new trials I should know about, in order to better help my patients?” Instead, he seems to know almost nothing about the clinical trial landscape. There are also some good research centers in Arizona: HonorHealth Research in Scottsdale, Ironwood Cancer Centers, or the University of Arizona Cancer Center in Tucson.

Problems like mine are common, and HNSCC patients commonly experience recurrence and/or metastases (“About 50% of these patients will experience a recurrence of disease. Recurrent/metastatic SCCHN have poor prognosis with a median survival of about 12 months despite treatments”).

If a lot of patients wind up failing conventional treatments, like me, then it would seem logical that helping those patients find a good clinical trial should be part of the standard of practice, and even standard of care, for HNSCC oncologists.

Discussing how clinical trials work with a patient before the patient needs one is also important for improving the number of trials a patient is eligible for—and the speed with which the patient gets into a trial. If a conscientious oncologist knows that their patient is open to a clinical trial and knows what clinical trials are available at the time of a patient’s recurrence, they might be able to get that patient directly into a trial. Early action is particularly helpful because a number of phase 1b/2 clinical trials combine the experimental treatment with standard of care, but only if the patient has not yet received standard of care. How can the patient into a study so quickly? Their oncologist has to know about it at the time of diagnosis.

To use myself as an example, at Ironwood Cancer Center there’s a promising phase 2 trial of an anti-CD47 antibody called magrolimab for HNSCC patients. It combines the antibody itself with chemo and pembrolizumab (Keytruda), but only patients who haven’t had pembro are eligible. I have had pembro, so I’m not. Given the circumstances under which I had it—as a crash measure to try and improve matters before the massive May 25 surgery that wound up taking my whole tongue—I wasn’t a great candidate due to timing problems. Other patients, though, who don’t need or get surgery fast as I did, might benefit greatly from the magro trial. I got a “hot” PET scan on April 26. If I’d been told on or near that day: “Get an appointment to establish care at Ironwood Cancer Center and HonorHealth Research; if that hot PET scan is confirmed, you want to be in a position to combine a clinical-trial drug with pembro,” I would’ve done so. Pembro on its own only helps about ~20% of HNSCC patients, according to the big KEYNOTE-048 study.

Not telling patients to get ready to attempt clinical-trial drugs in the event of recurrence is insane.

I will note the important caveat that a lot of cancer patients who reach the end of conventional treatments aren’t good candidates for the kind of intensive clinical trial search and entry that Bess and I did. Most clinical trials require patients who have good mobility, life expectancies longer than 12 weeks, no metastases in places like the brain or spine, etc. A lot of cancer patients are elderly and immobile; for them, discontinuing care and making their peace makes sense. The financial challenges are also substantial. I’ve been fortunate to get a lot of support via a Go Fund Me that my brother set up, but a lot of people are likely prevented from doing out-of-state clinical trials due to financial challenges. but not everyone.

So what’s going on? Do most oncologists know their area’s clinical trials, and my read of the situation is wrong? Is HNSCC unusual? Is my assumption that most oncologists will see a reasonable number of people who fail conventional treatments and want to do the best trials wrong?

It’s possible that oncologists are just lazy, but after four years of med school, three of internal medicine residency, and three of oncology fellowship, I’m going to discount “lazy.” A much larger number are likely burned out, a subject I address some in “Why you should become a nurse or physicians assistant instead of a doctor: the underrated perils of medical school” from back in 2012. Maybe few patients demand help with clinical trials, and consequently few oncologists provide real help?

2. Hospital center sites and/or drug companies don’t appear to do much outreach to community or even specialist oncologists. It wouldn’t take much for hospital research centers and/or drug companies to find oncologists, or even oncology support staff, in the larger region of a given trial site and try to say: “Hey, here are the better and more promising phase 1b / phase 2 trials we’ve got.” Bess and I were told, repeatedly and independently, that it’s not worth traveling or moving for typical phase 1a does-finding trials, which seems accurate, but for us it sure is worth moving or commuting for the most promising trials. There are likely many others in our position, too.

In terms of outreach, let’s use HNSCC as an example. How many head and neck cancer doctors can there be in the greater Phoenix area? 15, 20, maybe 30? It’s a highly specialized field. HNSCC is the sixth- or seventh-most common type of cancer, so it’s up there but far from number one. Phoenix, Tucson, Las Vegas, and Reno are all within easy commuting distance by plane to San Diego, and someone who prefers driving could commute that way. The petosemtamab trial I’m in at UCSD is probably the best available experimental treatment for HNSCC, and UCSD also has the BCA101 trial, which is another promising EGFR attack \ bispecific antibody. UCSD doesn’t seem to conduct a lot of deliberate outreach, or, if they are, it’s not reaching the oncologists Bess and I have been talking to. I don’t want to pick on UCSD—they’ve been great—and it seems that no clinical trial sites are doing substantial outreach.

If I were UCSD, I’d keep a list of the community oncologists of all the incoming patients. I’d send emails to those oncologists and their PAs every two or three months. It could be simple: “Hey Dr. Savvides—your patient Jake Seliger is doing well on the petosemtamab trial, and instead of dying rapidly, as expected due to the growth of his tumors, he’s able to live a somewhat okay life. If you have similar patients, please send them our way!” Yes, I know about HIPAA, and UCSD should get patient permission to do something like this.

I’ve seen speculation that hospital systems don’t want their oncologists sending patients outside the hospital system. So Mayo wants to keep its patients in-house, HonorHealth does the same, and so on with big hospital systems in every area. To put it bluntly, this is just keeping a patient and their insurance card close, only to watch them die.

It would not be hard for trial sites to hire search engine optimization (SEO) specialists and target pages at keywords likely to be of interest to persons searching for clinical trials. It wouldn’t be hard to bid on Google or Facebook ads targeting patients. To my knowledge, no trial sites do.

HonorHealth has been really good about keeping in touch with Bess and me via email and phone calls, which I appreciate.

3. Clinical trial sites don’t try to get their doctors licensed in other states.

If I were the boss at UCSD, I’d be paying for and facilitating my oncologists getting licensed in, say, Arizona and Nevada. If I were the boss at somewhere like HonorHealth Research, I’d want my docs licensed in California and Nevad. It’s not that hard or that expensive to get licensed in other states. Bess has done it! A lot of states are now taking part in the “licensing compact,” so that a doctor who gets licensed in state x can also practice in ten other states if they’re willing to pay the license fees.

Being licensed across state lines would allow those oncologists to see patients and screen them for potential trials at their institution from those states, likely via telemedicine. If insurance companies won’t pay for care across state lines, then it might be worth either eating the cost of the initial visits or charging a relatively nominal cash fee, like $100 or maybe a couple hundred bucks. This is, again, pretty low-hanging fruit of the kind that I’d expect a lot of businesses to be able to identify and knock down.

I’ve been told that a lot of clinical trial sites want to keep their patient rosters high and face pressure to get enough patients. I’ve heard from many principal investigators (PIs) that it’s difficult to fill a trial. It’s got to be hard to fill spots if patients are being aggressively disincentivized from joining at every step. How many are doing any of the things listed above? How many have created search-engine optimized pages for their trials? This isn’t costly relative to the expense of doctors, hospital care, intake, etc. The kinds of relatively minor changes I’m talking about won’t cost millions. An Arizona medical license can be obtained for $550 and a fingerprinting fee, and then it’s good for a couple of years.

On Facebook, one doctor said that there’s a lot of concern about “coercion,” and one doctor noted:

“Granted, hands are tied in lots of instances because it can’t come across as coercion. I would love to give your “insights” to our patients. Thank you for thinking of others while you are in the midst of everything.”

I’m not sure what specifically she means by “it can’t come across as coercion,” and when Bess asked she didn’t get a reply. Also, come across to who? How? Is the author worried about drug companies, the FDA, IRBs, or some other actor? Too much “coercion” is probably bad, but it doesn’t seem to me that trying to inform oncologists about relevant clinical trials is coercive. I personally would like some more coercion in this field, if it means I might learn about treatments that could save my life and the lives of people who come after me.

Still, I think that doctor is right about the way a lot of doctors think, or, worse, how a lot of administrators think; it’s easy to blame “HIPAA” or “coercion” or, worse, “medical ethics” for stasis. What passes for “medical ethics” is basically a joke, as shown most obviously during the pandemic, and when people cite “medical ethics,” they are almost always bizarrely non-specific about what “medical ethics” they mean, where those “medical ethics” come from, who upholds and interprets them, how they are evaluated, what “medical ethics” say about trade-offs, etc. There also seems to a be powerful, poorly supported paternalism that runs through the notion of “medical ethics.”

In my first public essay about me dying from recurrent / metastatic HNSCC, I talked about the FDA’s role in blocking medicines and consequently killing patients. The FDA’s villainy, which like so much villainy calls itself “good,” as in, “We’re denying you rapid access to potentially life-saving treatments for your own good, so please enjoy being protected while you die,” is the focus of that essay, but if we discount our ability to change the FDA, where else should we focus our attention? Changes at the margins ought to be possible, like those I’m proposing here. So far, this comment is one of the best I’ve seen about why change is hard.

It may be that most people are okay with the current state of affairs. Complacency and “good enough” define our age. There are real improvements over time—pembro is a miracle drug for a lot of people, to use one example, and although mRNA cancer treatments will probably arrive too late for me, they are likely to arrive at some point. If those real improvements move more slowly than they ought to, most people are okay with that, at least, until they or their loved one is dying of the disease.

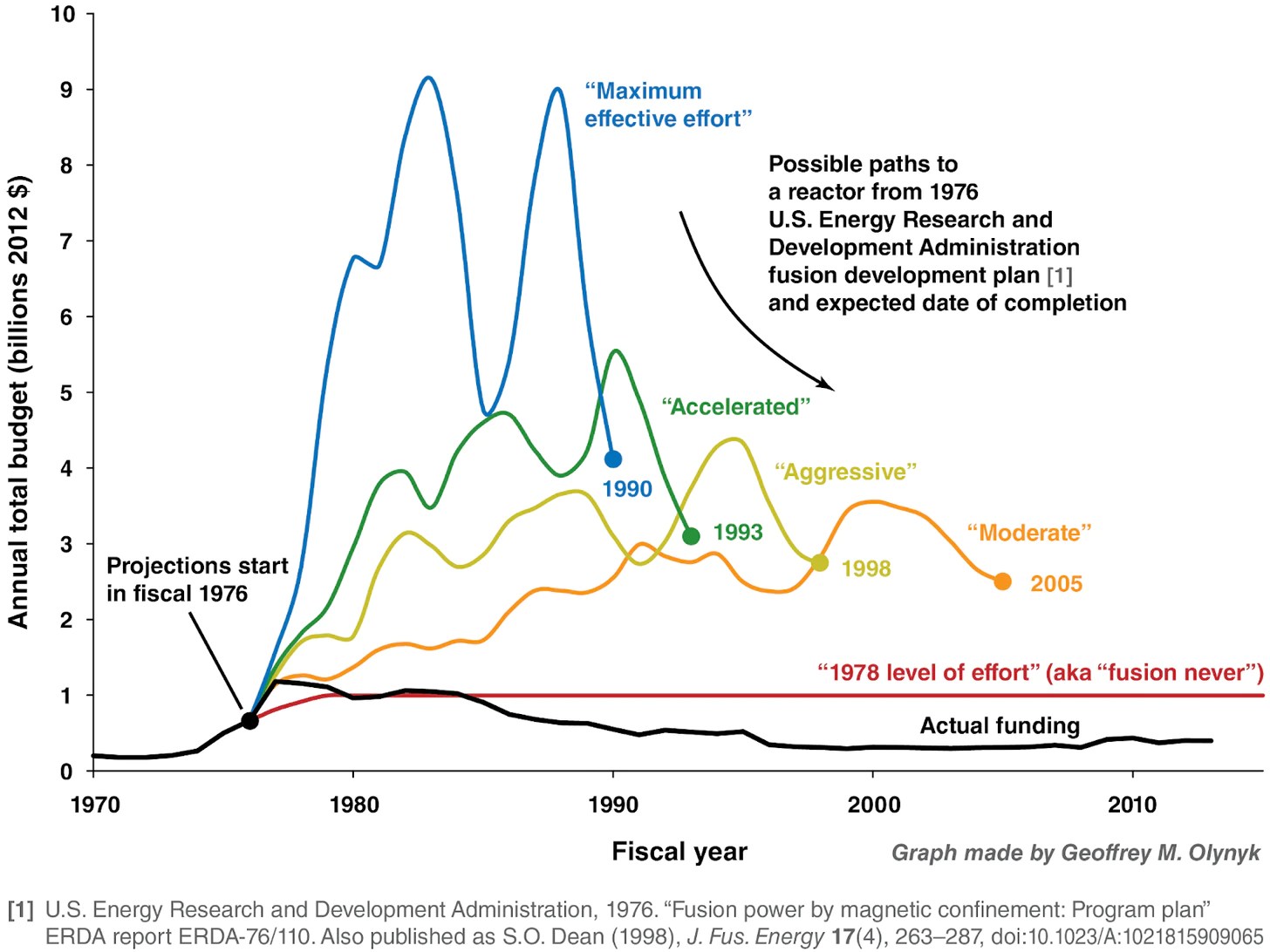

This is kind of like how the crappy transit systems in the United States are enabled by widespread cost disease. Transit nerds know that NEPA is a huge problem for both transit applications and clean energy applications, but NEPA reform remains frustratingly out of reach. Even the few cities that really depend on good transit, like New York, can’t generate the institutional motion to reduce the cost of building out subways and thus allow the building of more. The U.S. can and should do better at transit, but the median voter can go get in his or her car and drive to wherever. Sure, the traffic might suck. Sure, there might be better ways. But the current way is good enough, and good enough has become good enough in a lot of the United States. Sometime in the 1970s, we became culturally uninterested in the future, in the possibilities of material abundance, and in making the world better for our children. I think we should switch back to having a sense of urgency and importance about the future, including the future of medicine.

I’ve already lost my tongue. My neck mobility is probably 30% of what it used to be, and it’s criss-crossed by constricting scars. I’ve lost forty pounds that I can’t seem to gain back. Even the treatments that are in clinical trials right now are only likely to slightly prolong my life, not save it. I’m a dead man walking, but maybe the next person won’t lose his tongue. In another world, petosemtamab (or Transgene’s TG-4050) was already widely available in October 2022.

In that imaginary world, I got the first surgery, which removed only a part of my tongue, and then got petosemtamab orders along with radiation. The petosemtamab killed enough of the remaining cancer cells that I kept my tongue and didn’t need the second surgery. I’m working normal hours and eating normal food. I’m not concerned about the child Bess and I are working on creating will enter this world after his or her father departs it. That alternate world exists in a space where the FDA moves faster and there’s greater urgency around moving treatments forward.

I’m open to and interested in explanations other than the ones Bess and I have posited.

If you’ve gotten this far, consider the Go Fund Me that’s funding ongoing care. In addition, for more on these subjects, see “Reactions to ‘Please be dying, but not too quickly’ and what clinical trials are like for patients.”

* Even absentee ballots probably won’t help much.