The Undoing Project is entertainingly written, appears well-researched, and is also tremendously important—three things that, while not intrinsically opposed, occur together too infrequently. It’s so funny that I burst out laughing during class, while students were engaged in peer review, and every pair of eyes turned to me. I wanted to stop myself but couldn’t. It’s the best book I’ve read in recent memory and you should stop whatever else you’re doing to read it.

The “tremendously important” part is important for many reasons, one being that most people don’t seem to even know the (many) biases humans are prone to, let alone that knowing the biases often isn’t enough to change the behavior. We can understand the problems and still not turn understanding into action.*

The “tremendously important” part is important for many reasons, one being that most people don’t seem to even know the (many) biases humans are prone to, let alone that knowing the biases often isn’t enough to change the behavior. We can understand the problems and still not turn understanding into action.*

Still, there are steps we can consciously take to attempt to minimize or combat our biases. For example, “People had trouble seeing when their minds were misleading them; on the other hand, they could sometimes see when other people’s minds were misleading them.” That means we have to minimize hierarchy in many situations; empower people to speak up when they perceive problems; and listen to those who have differences of opinion, even if we want to immediately assume they’re wrong.

There are too many good sections in the book to cite them all. One example:

People did not choose between things. They chose between descriptions of things. Economists, and anyone else who wanted to believe that human beings were rational, could rationalize, or try to rationalize, loss aversion. But how did you rationalize this? Economists assumed that you could simply measure what people wanted from what they chose. But what if what you want changes with the context in which the options are offered to you?”

Conveying the humor in The Undoing Project is hard, maybe impossible, because so much of it is embedded in larger stories.

“Amos approached intellectual life strategically, as if it were an oil field to be drilled, and after two years of sitting through philosophy classes he announced that philosophy was a dry well. ‘I remember his words,’ recalled Amnon. ‘He said, “There is nothing we can do in philosophy. Plato solved too many of the problems. We can’t have any impact in this area. There are too many smart guys and too few problems left, and the problems have no solutions.”’”

I wonder if English lit suffers from the same (or a similar) problem. There’s been little progress since the advent of close reading, and the development of “critical theory” or “theory” is often if anything a step back. If there is anything interesting going on right now it seems to be in some aspect of applying computers to literature, but that is likely more a CS problem than an English lit problem.

We do get an ethnology of academia, too. Like:

Economists were brash and self-assured. Psychologists were nuanced and doubtful. ‘Psychologists as a rule will only interrupt a presentation for clarification,’ says psychologist Dan Gilbert. ‘Economists will interrupt to show how smart they are.’ ‘In economics it is completely normal to be rude,’ says economist George Loewenstein. ‘We tried to create a psychology and economics seminar at Yale. We had our first meeting. The psychologists came out completely bruised. We never had a second meeting.’ In the early 1990s, Amos’s former student Steven Sloman invited an equal number of economists and psychologists to a conference in France. ‘And I swear to God I spent three-quarters of my time telling the economists to shut up,’ said Sloman. ‘The problem,’ says Harvard social psychologist Amy Cuddy, ‘is that psychologists think economists are immoral and economists think psychologists are stupid.’

There seems to be no solution.

There also seems to be no solution for the systematic errors in human cognition. As I noted above, awareness is not enough. Even imagining possible futures is not enough, because one may come to predominate and stifle the others before they can be explored:

What people did in many complicated real-life problems—when trying to decide if Egypt might invade Israel, say, or their husband might leave them for another woman—was to construct scenarios. The stories we make up, rooted in our memories, effectively replace probability judgements. ‘The production of a compelling scenario is likely to constrain future thinking,’ wrote Danny to Amos. ‘There is much evidence showing that, once an uncertain situation has been perceived or interpreted in a particular fashion, it is quite difficult to view it in any other way.

The parallels to present world politics are too clear. We have forgotten the lessons of totalitarianism in just a generation and a half. We are too fond of constructing Kahneman’s rosy scenarios, which replace probability judgments. The probability of nuclear conflagration has grown in recent times. Yet we discount it. Recent elections in the U.S., U.K., Poland, and Hungary are systematic cognitive errors writ large.

The number of cognitive errors we’re subject to staggers. It’s “not just that people don’t know what they don’t know, but that they don’t bother to factor their ignorance into their judgments” (192). This book should above all make us doubt ourselves more, and especially doubt ourselves even when we think ourselves sophisticated. Over and over, we see people who receive training in statistics make basic statistical errors. We see people violate the law of small numbers.

I cannot recall all the times I’ve explained sample bias problems to people—rarely clients but more often students or friends—only to sense that no one is getting what I’m saying, or, if they do get it, they don’t care. The more one understands recurring cognitive weaknesses the more one sees them, the more I worry about succumbing to them myself. I myself succumbed to them in the last election, by substituting the opinions of people who are readily observable around me for the opinions of the much larger political body. And I myself wonder how often people have explained cognitive biases to me, or pointed out cognitive biases in action, only for me to ignore them.

The secret to the successful friendship between Kahneman and Tversky seems to have been pleasure: “‘We just found each other more interesting than anyone else,’ said Danny. ‘Even if we had just spent the entire day working together.’ They’d become a single mind, creating ideas about why people did what they did, and cooking up odd experiments to tests them.” The joint mind: It seems beautiful. I wonder how many of us accomplish such a feat. Lewis does cite a writer who began a book about productive pairs but never finished it. Another writer, Joshua Wolf Shenk, wrote and published Powers of Two: Finding the Essence of Innovation in Creative Pairs.

Lewis quotes his beautifully articulate subjects: “It is sometimes easier to make the world a better place than to prove you have made the world a better place.”

This is a kind of boring NYT review. This is a better New Yorker review, from Cass Sunstein and Richard Thaler, who are both cited repeatedly in the book itself. For example:

[Cass] Sunstein was particularly interested in what was now being called ‘choice architecture.’ The decisions people made were driven by the way they were presented. People didn’t simply know what they wanted: they took cues from their environment. They constructed their preferences. And they followed paths of least resistance, even when they paid a heavy price for it.

How are you paying?

* Maybe the robots do deserve to win.

Despite the chopped narrative problem, however, Dreamland covers important developments around opioid addiction and its origins. The better sections are arresting; for example, the description of the Xalisco traffickers could be from a business case study, as the Xalisco organizations respond to a number of different factors: supply and demand, a difficult regulatory environment, and unique managerial challenges (the best business case studies are themselves little novels, with the artistry that implies).

Despite the chopped narrative problem, however, Dreamland covers important developments around opioid addiction and its origins. The better sections are arresting; for example, the description of the Xalisco traffickers could be from a business case study, as the Xalisco organizations respond to a number of different factors: supply and demand, a difficult regulatory environment, and unique managerial challenges (the best business case studies are themselves little novels, with the artistry that implies). It’s hard to believe that all of My Secret Life is true, and it’s also hard to believe that it is wholly imagined. Today one might call it “creative nonfiction,” which seems to be a phrase that loosely means or connotes truthy, or specious, or “I need to make shit up to make the narrative more compelling.”

It’s hard to believe that all of My Secret Life is true, and it’s also hard to believe that it is wholly imagined. Today one might call it “creative nonfiction,” which seems to be a phrase that loosely means or connotes truthy, or specious, or “I need to make shit up to make the narrative more compelling.” Perelman was born into Soviet Russia, a place where the professional study and practice of math were frequently under peril. Soviet math survived Stalinism and the horror of the Soviet Union more generally in part from luck and in part from need, but they suffered from being cut off from the rest of the math world. Still, as Gessen writes:

Perelman was born into Soviet Russia, a place where the professional study and practice of math were frequently under peril. Soviet math survived Stalinism and the horror of the Soviet Union more generally in part from luck and in part from need, but they suffered from being cut off from the rest of the math world. Still, as Gessen writes: Making a “declaration” might not have any effect, but choosing to live one’s life the way one wants should presumably have an effect—or it would in a person of greater determination. In the blockquote above the word “organize” is also interesting. Is sexuality like a sock drawer, to-do list, or essay? Part of me hopes not but part of me wonders whether it might be.

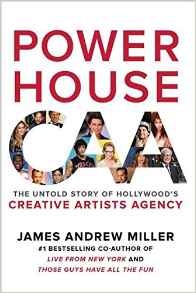

Making a “declaration” might not have any effect, but choosing to live one’s life the way one wants should presumably have an effect—or it would in a person of greater determination. In the blockquote above the word “organize” is also interesting. Is sexuality like a sock drawer, to-do list, or essay? Part of me hopes not but part of me wonders whether it might be. So why write about it at all? The book is going to be of great interest to anyone involved in startups, law firms, consulting practices, or changing industries. CAA rode a number of waves and mastered a number of key and unusual businesses practices, and it perceived how to adapt to a changing media and business landscape in a way that most of its competitors did not. In another world this could be a Harvard Business Review case study.

So why write about it at all? The book is going to be of great interest to anyone involved in startups, law firms, consulting practices, or changing industries. CAA rode a number of waves and mastered a number of key and unusual businesses practices, and it perceived how to adapt to a changing media and business landscape in a way that most of its competitors did not. In another world this could be a Harvard Business Review case study. These groups must also expand their size and scope, and convince others, none of which are easy: Most people are not ideological (or they are subconsciously ideological) and just don’t care. People who really care about and attempt to implement ideology in their own life are rare. Many also espouse an ideology but live contrary to it; socialists for example rarely got past this challenge.

These groups must also expand their size and scope, and convince others, none of which are easy: Most people are not ideological (or they are subconsciously ideological) and just don’t care. People who really care about and attempt to implement ideology in their own life are rare. Many also espouse an ideology but live contrary to it; socialists for example rarely got past this challenge. The book is also pleasant because Wolfram does not adhere to the false art-science dichotomy. He’s “spent most of my life working hard to build the future with science and technology.” At the same time, “two of my other great interests are history and people.” Idea Makers covers all four and to some extent asks

The book is also pleasant because Wolfram does not adhere to the false art-science dichotomy. He’s “spent most of my life working hard to build the future with science and technology.” At the same time, “two of my other great interests are history and people.” Idea Makers covers all four and to some extent asks