Susan Engel’s Teach Your Teachers Well completely misses the point. She says:

And if we want smart, passionate people to become these great educators, we have to attract them with excellent programs and train them properly in the substance and practice of teaching.

But the problems with teacher training probably have less to do with teacher training and more to do with institutional structures and incentives within teaching itself.

She says, “Our best universities have, paradoxically, typically looked down their noses at education, as if it were intellectually inferior.” The reason they probably look down upon education is that most educators, in the sense of public school teachers, have little incentive to excel at teaching once they earn tenure; consequently, most don’t. There’s been a lot of material published on this subject:

- Steven Brill describes the problem in “The Rubber Room: The battle over New York City’s worst teachers” for the New Yorker.

- Malcolm Gladwell shows the problems with looking at predictors of teacher success in “Most Likely to Succeed: How do we hire when we can’t tell who’s right for the job?“

- The Atlantic: “What Makes a Great Teacher?“

- In the L.A. Times, Jason Song says “Failure gets a pass” in “Firing tenured teachers can be a costly and tortuous task: A Times investigation finds the process so arduous that many principals don’t even try, except in the very worst cases.”

- Along the same lines, the L.A. Weekly describes “LAUSD’s Dance of the Lemons: Why firing the desk-sleepers, burnouts, hotheads and other failed teachers is all but impossible.”

- Megan McArdle talks about improving education on her blog, which also links to a piece from the Economist. See also her post “How Unions Work.”

- Ray Fisman in Slate: “Hot for the Wrong Teachers: Why are public schools so bad at hiring good instructors?“

- The New York Times looks at “Building a Better Teacher” and comes to conclusions not dissimilar from the others.

- New York Magazine explains the problems with teachers’ unions in the City.

- Maybe parents have a greater role than we think. But we as a society can’t do much to change or optimize parents; we can, however, do a lot to change and optimize schools and teachers.

- Clean Out Your Desk: Is firing (a lot of) teachers the only way to improve public schools?. Short answer: probably. Notice the various studies cited by the article.

- An [L.A.] Times analysis, using data largely ignored by LAUSD, looks at which educators help students learn, and which hold them back.

- Schools: The Disaster Movie: A debate has been raging over why our education system is failing. A new documentary by the director of An Inconvenient Truth throws fuel on the fire.

- “The Failure of American Schools,” also from The Atlantic.

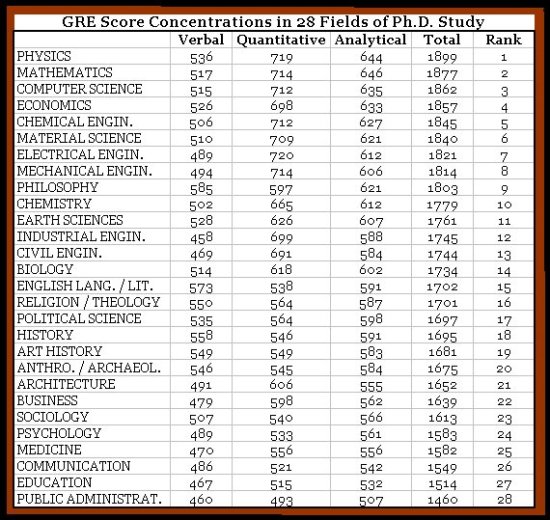

Taken together, these pieces paint the proverbial damning indictment of how teaches are hired, promoted, and (not) fired. Once you’ve read them, it’s hard to accept the dissembling evident from teachers’ unions. Given the research cited regarding the importance of good teachers and how few incentives there are to become a good teacher, maybe it shouldn’t be a surprise that education majors and graduate students typically have incredibly low standardized test scores and GPAs, as shown in the following chart (2002; source):

Notice that education is at the bottom. Should it be much of a surprise that the best universities, which are almost by definition hyper-competitive, look down on the profession? Susan Engel thinks so.

If you change the incentives around teaching, the programs that teach teachers will change, and so will the skill of the teachers more generally. Over the last thirty years, the larger economy has undergone a vast shift toward greater competition and freer markets—a vast boon to consumers. The market for primary and secondary education has seen virtually none of this competition, or, to the extent it has seen such competition, has seen it on a district-by-district level, which requires geographical moves to take advantage of it.

This topic is one I attend to more than others because I think I’d like teaching high school and that I might even be good at it. But the pay is low, even relative to academia (which isn’t most remunerative field in existence), and, worse, there’s virtually no extrinsic reward for excellence. Almost anyone with a slightly competitive spirit is actively driven out; even those who have it begin with probably lose it when they realize they’ll make the same money for less work than those with it. And you’ll basically have to spend an extra year or two and lots of money to get an M.A. in education, which sounds like a worthless degree.

If you teach computer science in most districts, you make as much as someone who teaches P.E. You might notice that, according to Payscale.com‘s average salary by major table, education majors usually start at about $36,200 and make a mid-career average of $54,100. That’s probably low because it doesn’t take into account the extra time off teachers get during the summer. Still, notice the numbers for Math: $47,000 / $93,600, Computer Science: $56,400 / $97,400 or even my own major, English: $37,800 / $66,900.

But I doubt money will solve the problem without institutional reform, which is very slowly picking up. Susan Engel’s comments, however, only muddy the water with platitudes instead of real solutions.

EDIT: And if you want further hilarity as far as teaching incentives go, check out Edward Mason’s story, “Union blocks teacher bonuses.” As Radley Belko says, “The Boston teacher’s union is blocking an incentive bonus for exceptional teachers sponsored by the Bill and Melinda Gates and Exxon Mobil foundations unless the bonuses are distributed equally among all teachers, good, bad, and average.”